The late, great David Lynch passed away one year ago today, and in a world where more and more people are watching movies on their fucking telephones, the cinephiles among us feel his loss just as profoundly as we did then. Luckily, Lynch left behind a stacked filmography of masterpieces, from the monochrome panic attack of Eraserhead to his bittersweet swan song Twin Peaks: The Return.

The span of Lynch’s cultural impact stretched far beyond his own works and into the media landscape as a whole, his style so distinctive it spawned its own descriptor: Lynchian, a term up there with “Kafkaesque” and “Machiavellian” when it comes to (unintentional) misuse.

Socially awkward interactions, misplaced musical cues, and a sense of dreamy surrealism undercut with moments of graphic, intense violence are all common thematic and aesthetic motifs associated with the term, while visually, the sight of a cup of black coffee, manicured rose garden or chevron-patterned floor will have any newbie film scholar doing the Leonardo DiCaprio meme-point at the screen. Yet, a screaming blonde woman alone does not a “Lynchian” film make.

The first known use of the term Lynchian can be found in a September 1984 double issue of the film journal Cinefantastique and its retrospective of Eraserhead within, in which K. George Godwin asserts that the 1977 debut is “likely to remain his most distinctive, purely Lynchian film.” (In his defense, Mulholland Drive wouldn’t come out for another 17 years.)

As with any word that moves from a niche vernacular into a more general one, the meaning becomes diluted, and more so than ever in an era in which labels are helpful for packaging aesthetics up neatly for trend purposes. Over time, “Lynchian” has become erroneously synonymous with the term “weird”, acting as a catch-all adjective to describe any film or television series that moves, either intentionally or otherwise, outside of the boundaries of genre and trope expected of it.

In a 1996 issue of Premiere Magazine, novelist David Foster Wallace muses on the difficulty of defining “Lynchian” in any concrete terms, saying that “like postmodern or pornographic, Lynchian is one of those Porter Stewart-type words that's ultimately definable only ostensively-i.e., we know it when we see it.” And it's true – “Lynchian” is far more of a gut feeling than it is an easily charicterizable subgenre, a feeling that is far easier to pinpoint than its reputation suggests.

Take for example, Lynch’s 2007 campaign to have Laura Dern’s performance in Inland Empire recognized by the Oscars. The lovable eccentric set up shop on Hollywood Boulevard with a large canvas of Dern’s face to his right, and to his left, a cow.

Those who misunderstand the term Lynchian might have imagined this scene to be far more outlandish, perhaps expecting the director to bring along a sloth, a sea cucumber or any other more extravagant or “weird” creature. But the cow’s simplicity is, perhaps, where the key to defining Lynchian lies.

A cow is a plain, farmyard animal, so unremarkable that to see one in context typically warrants no reaction at all: the key word here being context. Removing the cow from its context and placing it in the unfamiliar territory of the busy streets of Hollywood is as Lynchian as it gets – a slight alteration of the expected that challenges the comfort zones of the pattern and routine focused human brain.

As Godwin summizes in the aforementioned issue of Cinefastique, “By shifting the familiar a few degrees over, Lynch knocks us off balance, and the resulting uneasiness forces us to reconsider what we normally accept without thinking about.” What makes a Lynch work Lynchian is this continued clash between the mundane and the unexpected, that more often than not leads to an uneasy co-existence between light and dark.

In Lynch’s most unnerving images – a prom queen wrapped in plastic, a rotten ear in a sea of soft grass, a violent psychopath weeping to a song by Roy Orbison – we are reminded that such polarity is inevitable, acceptable and necessary. To celebrate the beauty in this world, we have to recognize the bruises.

Lynch himself embodied this duality in his life. During a particularly formative period living in Philadelphia, he recalled living between a morgue and a diner, perfectly encapsulating that balance of sweet and sinister that would go on to define his work.

Those who met him were often struck by his nostalgic mannerisms, old-fashioned style and gentle courtesy, all of which stood in stark contrast to his unsettling, off-kilter and often violent works. The legendary Mel Brooks famously described Lynch as “Jimmy Stewart from Mars”, his boyish, all-American personality offset by an otherworldliness that we are all still attempting to understand.

While these themes of duality are easy to capture with visuals of doppelgangers, and exploration of the sordid belly of Americana easily depicted with a Los Angeles setting, too many Lynch-inspired films fall into the trap of thinking the term “Lynchian” is a straight shortcut into horror, when in fact, the sincere, inherent goodness within Lynch's worlds was always as, if not more, important as the darkness that dwells within.

In the hands of a lesser director, Twin Peaks could easily have slid off the rails into exploitation. The tale of a beautiful but troubled young woman, abused by her father and with a penchant for drug-fuelled partying, had all the potential to become something voyeuristically salacious. But Lynch never fetishized Laura, nor did he canonize her; he saw in her both darkness and light, and loved her for both.

Too often do those desperate to obtain that coveted label of Lynchian put heavy focus on fear, alienation and brutality. Lest we forget, among Lynch's favorite films were The Wizard of Oz and It's a Wonderful Life – both works of art that demonstrate an innate trust in people, and a profound hope that humanity's goodness will prevail.

That’s not to say that there are no instances of Lynchian-inspired art that correctly fit the definition, however. Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie’s 2023 horror-tinged drama series The Curse, which maintains an unrelenting yet somehow strangely serene overcurrent of anxiety all the way through until its genre-defying, beautifully spiritually ending, dissects the squeaky clean veneer of whiteness that paves over Indigenous communities, much as Twin Peaks did three decades prior.

Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow and its themes of warped nostalgia in media could serve as a companion piece to arguably any of Lynch’s works (not to mention the film’s core allegory of transness – lest we forget one of Lynch’s most powerful onscreen moments was a direct plea to transphobes to “fix [their] hearts or die”.)

There’s also the works of Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who is perhaps the only living filmmaker who can match Lynch’s unparalleled ability to turn the most mundane of spaces into arenas of nightmarish anxiety, although the Japanese auteur’s works are far more nihilistic, eschewing the thread of hope and humanity that runs through so many of Lynch’s films.

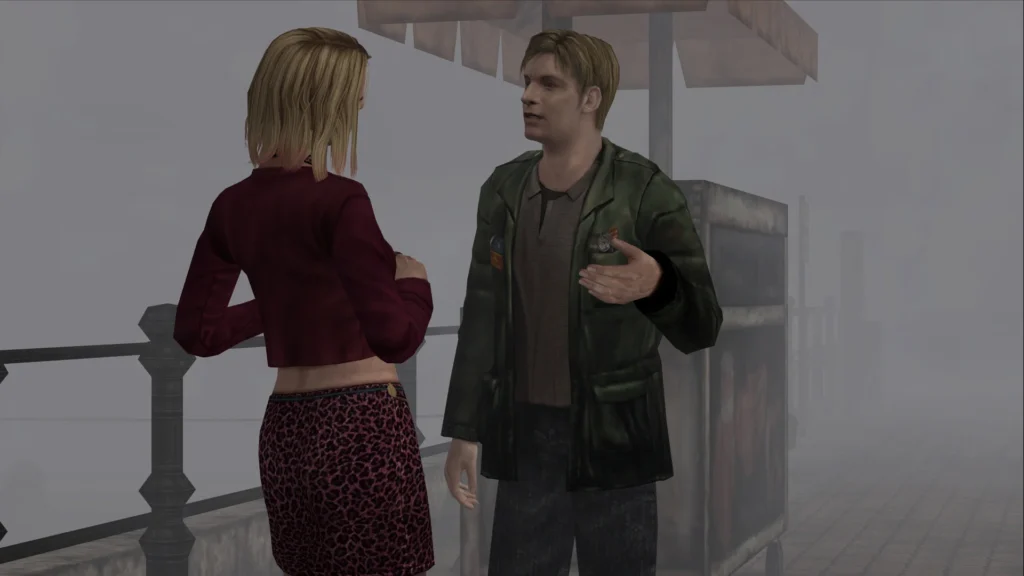

And thanks to their low-resolution graphics and uncanny, stilted movement of onscreen models, the original Silent Hill games nail a Lynchian feel even aside from their explicit Lynch references, of which there are many.

As we move into our second year of living in a David Lynch-less world, a world that feels at once smaller and scarier than ever before, the sincerest way we can honor the works of this misunderstood maverick is to preserve the legacy of the word Lynchian in accuracy. Demonstrate empathy. Believe victims, even if they don't look, sound or act the way they're “supposed” to. Embrace the weird and wonderful that life has to offer. Find beauty in the smallest things, and don't be afraid to fear.

And to any filmmakers reading this, please, for the love of god, stop trying to explain your work to us. Let the movie speak for itself, treat your audiences with dignity, and the assumption that we can handle morally questionable characters and complex stories without having our hands held. God knows our smartphone-rotted brains need the engagement. In the wise words of our late auteur, when demanded to elaborate on meaning and theme, your answer should be simple. No.