Editor's Note: This was originally published for FANGORIA on July 11, 2002, and we're proud to share it as part of The Gingold Files.

There’s a very funny scene early on in Reign of Fire, set in an ancient castle where the survivors of a 21st-century dragon-wrought apocalypse are eking out a medieval existence. The movie’s hero, Quinn (Christian Bale), and his friend Creedy (Gerard Butler) perform a crucial scene from The Empire Strikes Back, using makeshift armor and toy swords, for an audience of rapt, cheering children. The joke, of course, is that the setpiece is seizing the youngsters’ complete attention without benefit of any cinematic trappings. But in an indirect way, the joke is on Reign of Fire; take away the magnificent production, and there’s little here that would enthrall kids, not to mention adults.

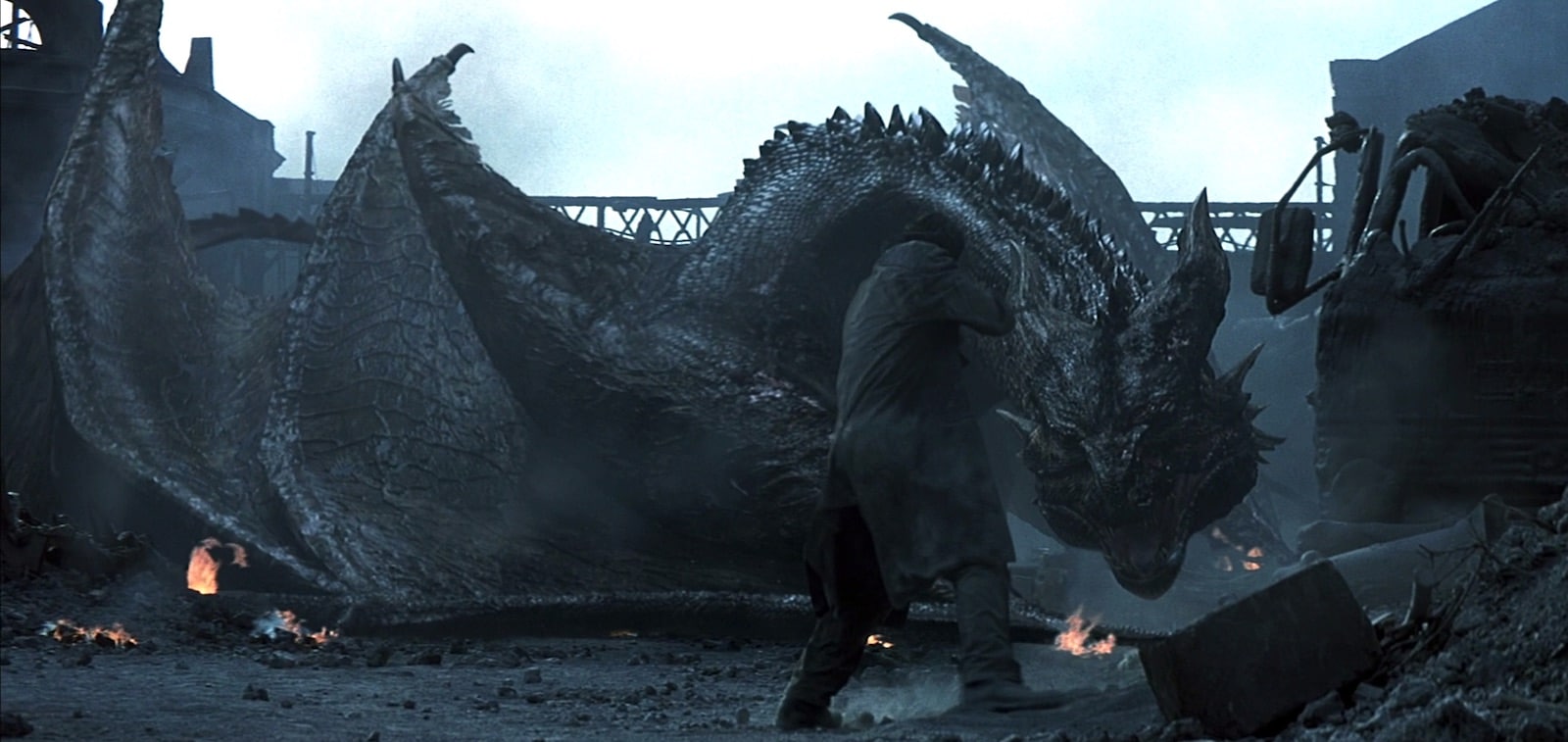

At many points, however, the movie’s technical achievements maintain a certain hold, thanks in part to director Rob Bowman’s serious approach to creating his fantasy world. Unlike, say, the Mummy films (and unlike next week’s Eight Legged Freaks), Reign doesn’t assault the audience with constant FX-for-their-own-sake or fourth-wall-breaking humorous asides that remind the audience they’re just watching a movie. A skillful early montage establishes the premise of a rebirth of dragons that raze the world’s cities despite mankind’s best efforts to stop them, and when the story proper begins, you don’t doubt that you’re experiencing a real world where flame-spewing monsters have practically scorched us out of existence. Wolf Kroeger’s production design of the dank castle and a ravaged London, coupled with handsome widescreen photography by Adrian Biddle (Aliens), immerse you in a compellingly plausible environment, and the CGI dragons (under visual FX supervisor Richard R. Hoover) are awesomely mobile, tactile and 100 percent believable.

Shame about the people, though. Reign sets up a rivalry between Quinn, who believes that holing up in the castle and waiting for the dragons to starve is the wisest option, and arriving American dragonslayer Van Zan (Matthew McConaughey), who’s rough and ready for hand-to-claw combat with the monsters. It’s a good basis for human conflict in the midst of the creature action, but the drama never (pardon the expression) catches fire. Neither the direction nor the writing gets beneath the surface, despite a particularly tragic backstory for Quinn: His mother (the welcome Alice Krige in a too-small role) was running a London construction dig that originally unleashed the creatures, and the film opens with the preteen Quinn witnessing her death as the first of the beasts blasts to the surface.

Equally shallow is the presentation of Quinn’s community and Van Zan’s military squad, whose members respectively lack the quirks, personality and rooting interest of The Road Warrior and Aliens (two evident influences). While the details of the physical environment have clearly been thought through at great length, the people who populate it remain ciphers, and barely anything resembling a subplot is allowed to distract from the key action. (This is the kind of movie whose end credits list almost every character by name, when appellations like “Second Dissenter from the Left” might have been more helpful.)

So it’s left to the dragons to carry the show, and while they’re kept offscreen entirely too much, when they do show up, they dominate the film as easily as they rule this scenario’s Earth. Bowman stages the man-beast confrontations with gusto, and one setpiece, involving a helicopter squad attempting to take down an airborne creature, achieves the outlandish, head-rush exhilaration of Shusuke Kaneko’s recent monster films from Japan. The inevitable final confrontation, once Van Zan puts into practice his theory on how to eradicate the dragons for good, also creates a few pulse-pounding moments—despite the fact that a) the solution seems rather too convenient and b) it’s impossible to believe that the world’s scientists and military couldn’t have figured it out long before Van Zan did.

The actors do as convincing a job as they can given the thin material; Bale cuts a fairly compelling figure, though it’s hard to tell whether the laughs McConaughey’s sometimes over-the-top performance elicits are intentional or not. As Cleery, Dracula 2000’s Gerard Butler has little to do but play the Best Friend, while the role of Van Zan’s helicopter pilot never allows Izabella Scorupco to stretch beyond Tough Babe conventions. (There’s an irony in the fact that the Bond Girl role in GoldenEye that launched her career actually provided her with a meatier part than her subsequent features have.) The presence of Bale, Butler and many Brits in the supporting cast add an Anglophilic angle that’s a pleasing novelty among Hollywood FX epics—but if you do see the film, be sure to pick a theater with good sound, since the heavy accents occasionally render the dialogue impenetrable even when it’s not competing with roaring fires and hissing dragons.