Like slime, worms make for fascinating movie monsters. They're impossible entities to relate to, existing in and experiencing the world in ways we can't fathom—not that many would want to anyway. Ecologically speaking, they're a sign that soil is healthy; that it's alive. But in storytelling, they function as potent signifiers of existential, embodied dread. We may all be systems of sentient goo underneath our skin, but worms are the things that eat the goo we turn into. Whatever your class or station in this world, we are all, in the end, worm food.

Horror creators- fiendish little freaks that we are- like to play with viewers' feelings by shoving their noses in this highly discomfiting truth. If you want to visually demonstrate a decaying body on screen, sure, you could just show the corpse or skeleton and some dirt. But if you really want to make folks feel like they ate something bad, then that corpse will be riddled, positively teeming with worms, maggots, and other flesh-eaters. A dance party will be happening between the rib cages. One will absolutely be writhing in an empty eye socket.

Mid-twentieth century ecohorror like The Birds and Jaws frequently juxtapose the banal idyll of the natural world with a violent, never considered, inexplicable disruption. Projects like Squirm and Slugs take their beats from this particular formula, where the humble worm is transformed into a nightmarish deluge with a voracious appetite for human flesh. This movement subverts the diminutive, lowly quality frequently prescribed to worms as denizens of the subterranean, disrupting these assumptions in unconsidered, terrifying, and outright gross ways. What would happen if all the worms underground suddenly rose to the surface?

While Squirm plays on the size and quantity of worms, David Cronenberg's Shivers and 1988's Slugs include the parasitism aspect, the truth being that not all worms are our friends. Far from your standard ecohorror flick, the worms in Shivers are experimental man-made parasites developed in a failed attempt to treat organ failure. Rife with distinctly Cronenbergian themes, Shivers shares DNA with projects like The Faculty, which, in its adaptation of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, features worms that double as an army of parasitic alien body snatchers, the worm-as-parasite being its own category also seen in projects like Possession, Slither, and The Strain.

Then there's the giant worms. While the camptastic graboids of the Tremors franchise are likely front of mind, 1981's Galaxy of Terror features an infamously exploitative rape scene involving an enormous alien worm that doubles as a slime monster. Ken Russell's The Lair of the White Worm is based on Bram Stoker's 1911 novel of the same name and taps into medieval storytelling traditions in its presentation of monstrous figures that are equal parts worm, dragon, snake, vampire, and pagan god.

And despite being extremely different characters in their respective narrative contexts, the divinity prescribed to Dionan is also present in Dune's Shai Halud: the great sandworm deified by the Fremen. The contradiction of this tension between ignobility and reverence is what makes worms and their depiction in horror films so interesting.

As often as monsters have been weaponized to code and incite violence against the disenfranchised, so too are they used to convey truthfully the more metaphysical aspects of existence and experience. In recent years, “brain worms” have been the go-to explanation for the wildly pervasive moral and spiritual rot that infects a considerable portion of the human population, symptoms of which include nonsensical babbling, rage that foams at the mouth, a taste for libidinal violence, and cannibalistic tendencies overall. Consider how the language we use to denote hatred of specific groups is framed through the rhetoric of mental illness: words like transphobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia. And still, “brain worms” feels more accurate.

In 2009, Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan published the first of what would become a trilogy of novels, comics, and eventually a 2014 apocalyptic television series called The Strain. At its core, the project is a modernized adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula. To the same degree that Francis Ford Coppola's rendition reveled in the novel's romance, del Toro and Hogan capture the deeply unsexy essence of why vampires terrify: they are monsters of contagion. Vampirism is a highly transmissible infection that transforms its hosts into bloodthirsty parasites.

Over the centuries, vampires have been visually rendered in all kinds of ways, largely based on the thematic anxieties they're meant to embody. As monsters, they are by definition “oversignified.” So we read the vampire that allures, whose presence is attractive and intoxicating through tensions around gender and sexuality. But Stoker's Count, in particular, is largely informed by Victorian anxieties around disease, immigration, and what Jack Halberstam refers to as “bad blood” (which, of course, intersects with gender and sexuality). Strip away the xenophobic, antisemitic, queerphobic tensions that equate specific groups of people with disease, and what you're left with is the infection itself.

There are no sexy fangs or otherworldly beauties in The Strain. The ancient evil arrives in Manhattan aboard a “dead plane” whose inhabitants are infected with parasitic worms that devour their hosts' insides and transform them into, well, bigger parasitic worms; a transformation that follows a misleading incubation period where they appear dead but most definitely are not. Once turned, the new vampires are then compelled to seek out their loved ones, who can easily become infected whether fed upon or not.

Of all the diseases that plagued Victorian society (typhoid, measles, syphilis, and smallpox to name a few), tuberculosis- euphemistically referred to as “consumption”- was unique for the particular role it played in shaping the art, culture, and fashion of the nineteenth century. Not only did it influence beauty standards, leading to the exaltation of frailty and bloodless pallor in feminine bodies, but it also took on a symbolic association with creativity and the erotic, leading it to be euphemistically nicknamed “the romantic disease.” This prescriptive romanticism was further enhanced by its highly contagious nature and the fact that TB spread easily through close contact. People frequently brought it home to their families and neighbors.

It's worth mentioning that leeches were a popular treatment method.

These anxieties are all thematically present in Stoker's Dracula, and Del Toro and Hogan draw on this history- Stoker's influences- to illuminate how contagion begets many of the world's truest horrors. Moral monsters like Frankenstein's Creature or the Wolf Man have nothing on a parasitic virus. But what else is kept of Stoker's rendering is Dracula's association with extraordinary wealth and power. Or rather, his rendering of the bourgeoisie as an undead parasitic class that achieves immortality by feeding on the lifeblood of the proletariat. Indeed, Del Toro and Hogan double down on this characterization in The Strain while reframing specific aspects in ways that clarify Stoker's critique of power.

Through a combination of bureaucratic ineptitude and cabalistic subterfuge, the worms are released into New York City and the only ones to see the imminent threat are rogue CDC epidemiologists Dr. Ephraim Goodweather (Corey Stoll) and Dr. Nora Martinez (Mia Maestro), pest control exterminator, Vasiliy Fet (Kevin Durand), and Abraham Setrakian (David Bradley), a professor, pawnbroker, and Holocaust survivor who first encountered The Master (Robert Atkin Downes) and Thomas Eichort (Richard Sammel) as a young man in Treblinka.

The worms in The Strain are signifiers of spiritual corruption: a pathogenic insatiability, be it for blood, the pleasure of subjugation, or both. Because what's the difference in the end, really?

Del Toro is known for his beautiful, complex, often sympathetic monsters whose humanity is frequently deeper than many of his humans. But The Strain is a project of clinical absolutes. A straight line can be traced from procedural television to nineteenth-century gothic horror fiction that “sensationalized” actual events to reflect on and incite social change to various ends, and from which Halberstam's concept of “the technology of monsters” arises. Operating in this fashion, The Strain takes on that eerie, premonitory quality certain horror works possess this side of 2020, even as it treads well-worn genre themes and motifs. Consider the closing monologue from The Twilight Zone episode, “I Am The Night–Color Me Black”:

“A sickness known as hate. Not a virus, not a microbe, not a germ. But a sickness nonetheless, highly contagious, deadly in its effects. Don't look for it in the Twilight Zone. Look for it in a mirror. Look for it before the light goes out altogether.”

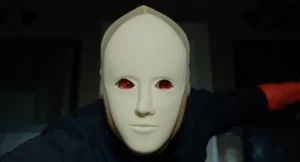

That same sentimentality about horror's power to shape our worldview has become characteristic of most of the genre's current rising stars. Like del Toro, Australian writer-director Alice Maio Mackay reveals an undeniably romantic sensibility about horror that's deeply reflected in T-Blockers: her take on the brainworm phenomena sweeping the globe.

T-Blockers is a horror lover's horror flick in that homage is part of its form. This is perhaps most evident in Mackay's nostalgic use of the traditional opening and closing monologues popular in classic genre fare [see above], but it's also evident in its narrative beats, which call back to movies like Squirm and Shivers. Derivation is a quality the genre is generally denigrated for, but in Mackay's hands, it's treated with honor. She knows she's part of a lineage.

Like Squirm, it starts with a natural disaster. An earthquake rocks a rural Australian town and, unbeknownst to residents, unleashes an infectious parasitic worm upon the community. Juxtaposed with the earthquake is the expansion of transphobic legislation that the film's queer trans protagonists must contend with in addition to a litany of other related horrors: fetishists and chasers, job and housing insecurity, self-sabotaging tendencies, and family dynamics in general. But from that struggle also comes, well, everything that makes a life.

There's an emotional and intellectual maturity to Mackay's handling of the subject. Sure, the worm-infected incels and hatemongers are the obvious monsters. But that isn't to say we aren't all battling our own particular brainworms.

This column's been a lot about brainworms as a vitriolic hatred projected onto others, but the limit truly does not exist. Dysmorphia and dysphoria are brainworms. Cynicism is a brainworm. The compulsivity associated with addiction is a brainworm. The need to assert your opinion on or even understand choices other people make for themselves about their lives that have no material effect on anyone else is a brainworm. The possibilities are endless, and so is the terror — but only if you let it eat you from the inside out.

Mackay refuses the temptation to prescribe moral purity to her characters, distinguishing the human by a warm, awkward, fleshy realism that contrasts the hollow insatiability of her monsters. Unconcerned with appealing to the “elevated horror” crowd, she embraces the genre's intensely queer history both thematically and stylistically, the project's campiness and punk ethos illuminating how horror has lit a path for society's weirdos, outcasts, and monsters for as long as it's existed. And in this way, it too is kind of a brainworm. It makes a home in you.