Last Updated on March 28, 2025 by Angel Melanson

In his fan letter published in The Hollywood Reporter last year, screenwriter John Logan (Gladiator, Penny Dreadful) said of Martine Beswicke, “In the long parade of horror cinema’s virginal ingenues, wan heroines, willowy victims, and helpless damsels-in-distress, Martine Beswicke stands apart. She is the most modern Scream Queen of them all — because she never screams, she never cowers, she never shrinks back. She is a dark, rakish silhouette made to trouble your dreams, to destroy you with her panache and make you glad you came to such an outré and stylish end. It’s hard to resist the force of nature that is Martine Beswicke.”

Who are we to argue with that?

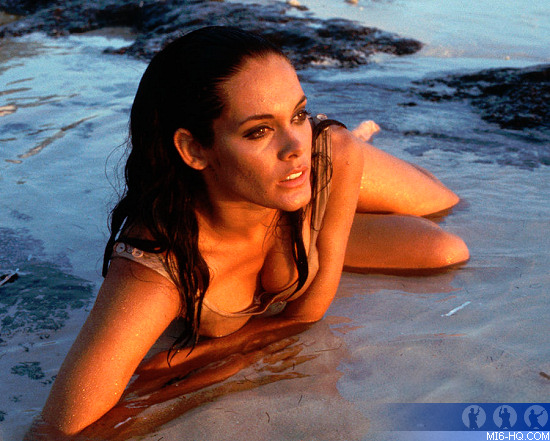

In a career that spans over 60 years, Ms. Beswicke (sometimes Beswick; a numerologist suggested she add the ‘e’) has made her mark on genre in a variety of projects: Two James Bond films, prehistoric pulp, Oliver Stone’s directing debut, and the iconic title role in Hammer Studios’ Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde. (And a Billy Joel music video!) A constant in all her work is an alluring, charismatic, and fierce-bordering-on-feral presence, with a glint in her eye that hints at the resolve and humor beneath.

This year she’s publishing her autobiography, On My Way, which is as raucous and endearing as it is human, giving a fuller picture of the enigmatic star than fans have ever seen before. FANGORIA was honored to sit with Ms. Beswicke for an extended chat about her career, life in the swinging ’60s, and what exactly fueled her unforgettable screen work.

The editorial that John Logan (Penny Dreadful) wrote about you in the trades last year was such a beautiful surprise to see. Did you know that was happening?

Well, my friend Sam Irvin, who’s a director, said ‘You know, John Logan is really quite mad about you.’ And I went, ‘Who’s he?’ He said, ‘Well, he’s co-written Skyfall.’ I said, ‘What? It’s my favorite Daniel Craig Bond film.’ And then I heard, ‘And then he did Penny Dreadful.’ I said, ‘What? This is one of my favorite shows.’ I was completely addicted. And he said, ‘Well, he’s very keen, and he’s going to write a tribute.’ I said, ‘Why?’ And the next thing I know, he puts us together, he writes his tribute and sends it to me. And literally, my heart is pounding. I can’t believe that this incredible, gifted man is writing this about me.

And then of course, now we’re in touch. We connected immediately. And then we met in person, and I adore him.

I have this running fascination with the idea of someone trying to reconcile with their own legacy, and the process of writing down your life story. Is it daunting? Is it sobering? You’re trying to make sense of your own life in a finite number of pages. What about that process surprised you?

Well, I tell you what was surprising was that I remembered more about my childhood in Jamaica than anything else. I remember so many details. I mean, even down to the tactile, physical stuff. So that was interesting.

It’s unfiltered and very candid, and we can practically hear you telling these stories. There’s a moment in the book where you’re interacting with someone from Jamaica who had worked with your dad, and I guess it would be called code switching now – you suddenly go into the patois a little bit. I think that a lesser project might’ve smoothed some of that over, and I love that you didn’t do that.

Authentic. It had to be authentic.

In the book’s foreword, Logan calls you a ‘shockingly modern presence’ in your earlier films. It’s really astute. There’s a presence and maybe even an awareness in your performances that suggests you’re playing by a different set of rules or maybe even a different game altogether than your co-stars. There’s something… ‘otherly’ about you in some of those earlier parts.

I was a wild child from an early age, and I do talk in the book about the fact that I was probably a feminist without even knowing what the hell a feminist was. I actually looked back at my films and… I hate the word ‘journey,’ but it really was like a marker of where I was in my life at the time. It’s quite interesting.

I did From Russia with Love and was this feral fighting girl, and at the time I was angry to think that men could do what they wanted and I couldn’t without being labeled. So there was a lot of my ‘how dare you!’ female power in the performance.

And it was there in Thunderball. It was always there. Because I think that it underlined really the fact that I looked out there and I saw what was going on. I don’t know anything too much about politics – mind you, I do go fucking mad these days. But I did then too, I mean about everything that was going on around me.

So I think there was a bit of a mark. Doing Prehistoric Women, Michael gave me the best lines to chew up the scenery and I chomped on them, but I really meant them. It was like, ‘How dare you? Do you think you’re going to make me do what you want? No, no, no.’ But it is there. I mean, obviously I don’t go around stabbing people and drawing blood. Maybe in my mind I do.

In the section on the Hammer film Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde, you write, ‘I realized at some point that not only had I some male in me, but that I was an alpha male.’ And what you’re talking about in conversations with your co-star Ralph Bates is that gender is a spectrum, which is not the language that was used back then, but you’re talking essentially about gender fluidity. I’m curious how you look back on that role in modern times, because I think it was ahead of its time in a lot of ways.

It was, actually. I think it was about three years ago, there was a whole group of university students that were doing something on gender transformation, and they used this film, and I thought, ‘That’s interesting.’ And of course you know that’s one of the things I wish we had gone deeper into, and later I was made right. Nice to be right sometimes.

You talk about the ’60s as a time of freedom, free thinking, open mindedness.

I mean, we were having fun and for me life should be a lot of fun. And I mean, even when things are bad and you’re crying and you’re like, ‘Oh my God, my life is over,’ there’s always that other little thing right next door that goes, ‘Oh my God, let’s go have some fun.’ And the ’60s for me was all about that. And everybody was in the same mindset.

They still considered me quite a goer; ‘She’s a right goer, that one.’ But I didn’t care, because I thought, ‘I’m having the best time. Listen, you guys think you can put it anywhere you want? Well, guess what? I’m going to put it anywhere I want.’

In the book, you talk about how you were kind of stranded and left to your own devices with an unsavory photographer during Thunderball, and you had a similar issue on Sister Hyde, where suddenly you find yourself in a room across from a man who’s trying to get you to disrobe. Coercion is the word I would use, or maybe that a prosecutor would use. But I’m curious about the reality of that in your career, especially against the context of the present, where it’s being more called out into the open.

Oh, I escaped. Are you kidding me? I escaped. I have a feeling it might have something to do with who I am. It might have something to do with ‘Battling Beswicke’ because that was the title I got. There were headlines in newspapers, ‘Battling Beswicke is at it again.’ I think there was a fierceness about me that kept the trolls away.

Sure. But you’re on a set and you’ve agreed to this, and then suddenly they want to do that – something beyond what was negotiated. And in the book you don’t take that for a minute. You stand your ground.

Absolutely. The thing is, too, they were not going to win. I’m quite happy to take all my clothes off because it can work, but not the way they’re going to film it. I have to say, I was lucky because I did not often find myself in those positions. In fact, what I had, which is quite interesting, were champions. (Bond director) Terence Young – we were best friends, and it had nothing to do with trying to bed me. Nothing to do with that at all. He and other people were literally my champions, and all men who might have taken advantage of me.

Maybe it was just the men that I came across because I didn’t come across that nasty piece of shit, Weinstein. I don’t know. I might’ve got a fucking knife out to him, really. I have friends who have been there, not with him, but with other people, and that was pretty horrible.

So I was lucky. But I think it also had to do with who I was, who I am.

A film of yours that I think not enough people have seen is Seizure, Oliver Stone’s first film as director.

I love that film. I loved it because it’s crazy like he was. I mean, it was based on a nightmare that he had. And making it was like being in a film. And oh, the people who were in it: Jonathan Frid, Mary Woronov, Hervé Villechaize.

It did seem like a stew of very different types of folks. Hervé Villechaize (who’d join you as a Bond alumni a year later) was a painter, Jonathan Frid was a television soap actor, Mary Woronov was an underground artist; it was such a hodgepodge of folks. But Oliver Stone, making his first film: how crazy was he allowed to be?

Well, first of all, he tried to bury it, and it can’t be buried. And the whole experience of the filming was as nutty as the actual content of the film. I mean, the fact that we all lived in the house, the fact that we all literally had to take care of each other; it was quite an experience. Because as I explain in the book, there are a lot of weird things that happened on that set.

What was Jonathan Frid like? He seems like he might not have been a ‘suffering fools gladly’ type of person, from what I know about him.

Well, we all loved him because he was a bit cranky, but I totally understand because he was in the main bedroom, and most of the equipment was in that bedroom. So he would wake up in the morning and go, ‘Oh, fuck, why can’t I have a proper bedroom?’ And I mean he would just complain and bitch and moan. He was a bit of a curmudgeon, but I love curmudgeons because you can really have fun with them. I’d say, ‘Oh, how are you doing today, Jonathan? Oh, I see you’ve got one less camera in here today.’ ‘Oh, (grumble grumble).’

And Hervé had a reputation as a lunatic, to put it bluntly. Was that your experience with him?

He was really cool, and he was really bright. And he also was a bit of a gentleman until his wife had an affair in Paris during filming, and then he turned into a maniac. When he heard from set that his wife had had an affair, that was the end. But still, he gave his all.

You’ve got this massive CV of film and television credits, but I only recently just found out that you’re also in the Billy Joel music video for ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire.’ How does that happen?

Well, apart from my regular theatrical agent, I also had a commercial agent, which of course, thank God, because that kept me from literally going to live under a bridge somewhere. So it just came up and suddenly there I was. And it was really bizarre. I have no idea. I was supposed to be, I don’t even know what I was supposed to be like the mother from hell. I still have no idea what it was all about, but he was very nice, and I liked his music, and it’s still playing. And every now and again, someone says, ‘Oh my God, you’re in…’ I said, ‘Yeah, I know. I know.’

Today was my turn; sorry. When you get into the ’90s with your career, suddenly the boys who were such fans of yours in some of your older films are now making movies, and then your phone starts ringing again to do these other projects. And one of those folks was Jeff Burr (From A Whisper To A Scream), who we lost a little more than a year ago.

He was just a lovely chap, really. I use the word ‘keen,’ but it’s more than that. He was really passionate about film. He was really passionate. So I felt like a mum in a way. I felt very maternal with him because he was quite a lot younger. I can’t believe that he’s now gone.

Yeah, he died in October of ’23. It was sad news.

And I had seen him just before that, I think. I liked working with him because these guys were really passionate about what they’re doing. It was lovely, their enthusiasm, especially because at that time, I was losing my passion. So to have those moments with these guys who were still passionate about their work and what they were doing was really… it was fun to be with.

On that note, if the phone rang tomorrow and some scrappy independent filmmaker wanted you out in front of the camera again, would you consider it?

I think I’m past it. In fact, someone recently asked, because now all of a sudden there’s John Logan who’s written this tribute that made me go into imposter syndrome immediately. And the next thing I hear is that Scorsese has put Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde on Hidden Gems of British Cinema. I just heard a few days ago that Peter Jackson, huge Bond fan, has a photograph of me on the wall, and I’m going, ‘What is going on? Am I being discovered at this late age in my life?’ And then somebody asked what you asked. And I said, ‘Well, here’s what we can do. No lines. I just arrive in full garb and maybe behind a palm tree. I just make my entrance and exit. That’s it.’

Just anoint the set with your presence and then go home.

Why not?

Are we going to see you at another convention someday?

Oh my God, yes. I have to say, I love doing them, and I particularly love doing it with my sister. I have a lot of sisters, but this is my number one sister, Caroline-

Yeah. When the Bond girls meet there is – to use a pun – there is a bond. We have a real bond because no one else has experienced this. There are a lot of other actresses who have done all sorts of other franchises and you know, but not a lot of people have done this.

Yeah, it’s a sisterhood that crosses generations and lines of race and nationality. It’s truly special that you guys all share that.

It is. When we are going to do a show, we always call each other, ‘Who’s going? Who else will be there?’ We’re like a bunch of little kids. I know some people don’t want to do conventions or they think they’re boring, but if we’re going to do a convention, we’re going to have fun. That’s it. Whatever we do, we’re going to have fun.

That’s a good policy.

I know it sounds like a cliche, but the one thing that keeps me afloat, really, is the love I have for my friends and they have for me. It is the one thing that keeps me sane, given the disaster that is happening right now around the world. I mean, there are times that I really can’t watch the news sometimes because I just get up and start marching down my hallway, swearing.

I did want to say, the one thing that really surprised me about the book was you told these anecdotes about living in LA during the Rodney King riots, and there’s a story of being robbed at your doorstep – there are some dark stories, but all told through this prism of empathy you have for other humans. I think that there’s a real lesson to be taken from you there.

I thought it was important to show all of that, alongside the follies and fun stories, so that people can see that we can definitely come back from some of the darker situations that we find ourselves in.

Some friends of mine said of this book, ‘Look, why don’t you talk about who you really are, and who you are is that you truly love people and your whole life is about love, and no matter what you did in terms of your work, your life was always about that.’ I thought that’s a good way to look at it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Martine Beswicke’s On My Way is available now.