Seventy years ago, the shadowy silhouette of Reverend Powell (Robert Mitchum) hummed “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” as he hunted for the Harper siblings on a West Virginia hillside. Yet, due to a number of unfortunate circumstances, the film was released in an environment that did not appreciate it as it is today. Director Charles Laughton would take the initial failure of his directorial debut personally and would never again direct a feature film. He would pass in 1962 before he could see its reappraisal into the pantheon of greatest films ever made. That film was The Night of the Hunter, and since July 26, 1955, the film has grown to such an enormity that it has influenced a host of modern-day greats. From Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing, to several Coen Brothers features, the influence of this titanic picture can still be felt today.

In the film, Reverend Powell is a serial killer who believes himself to be enacting “God's Will” by cleansing the world of sinners. While imprisoned alongside the Harper family's father, Powell learns of a secret stash of stolen cash and inserts himself into the family. As he tries to discern the location of that secret stash, he begins disseminating his own toxic interpretation of Christianity by marrying the recently widowed, and emotionally vulnerable, Willa Harper (Shelley Winters).

Powell uses her as a mouthpiece to propagate his own religious zealotry throughout the small town. He further espouses this archaic sentiment on their wedding night by positioning the Christian fundamentalist view that the female body is meant only for reproduction and that female sexuality must be contained. In the Journal of Religion and Film, Carl Laamanen notes that “These scenes, imbued with terror, condemn the patriarchal project of fundamentalist Christianity and illustrate how the Church and the Preacher oppress and repress Willa.” (p.10). Here, the danger, influence, and hypocrisy of Powell's religious zealotry are very real, ideas that horror has continually returned to.

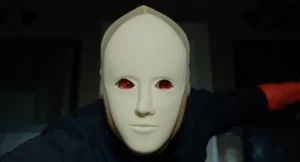

One such example of influence is Bill Paxton's patriarchal Meiks in Frailty. The Paxton-directed film exists as the perfect inversion of the 1955 film due to its parallels and repetition of several visual motifs, while also flipping these ideas on their head with the reveal in the finale. Meiks is a father besieged by visions of God commanding him to kill demons disguised as people.

These visions lead to a back-and-forth struggle with his two sons on the validity of his visions and the murderous intent behind them as the body count begins to rise. Meiks is eventually killed by his eldest son when attempting to murder a man accused of numerous violent acts, but only decades later is it revealed that the youngest son can also see the crimes committed by these “demons” and thus carries on the work of his father as the God's Hand killer. As a direct parallel to Laughton's film, where the villainous Reverend Powell uses religion and God as an excuse to punish those he deems “sinful”, in Frailty, Meiks' divine visions reveal to him the true evil of specific individuals. In essence, Powell is an evil man who punishes the innocent, whereas Meiks is an innocent man who punishes evil.

Other villains similarly influenced by the religious hypocrisy defined by Powell include the angel Gabriel (Tilda Swinton) in the 2005 comic book adaptation Constantine and Morfydd Clark's titular character in Saint Maud. Revealed in the climactic third act of the film, Gabriel is found to be complicit in the conspiracy to bring about Hell on Earth due to her jealousy at God's favoritism of humanity and her belief that humanity must be tested in order to earn God's love in the face of the Judeo-Christian apocalypse.

The irony in her hypocrisy is based on the fact that she is an angel descended from Heaven, working with the forces of Hell to assuage her very human emotions. Meanwhile, in Saint Maud, the character is defined by her religious zealotry in the face of mounting personal hypocrisy. As a private care nurse who is running away from her sordid past, her newfound devout beliefs are in constant friction with her new patient Amanda (Jennifer Ehle), whose hedonistic life she hypocritically tries to condemn.

This tension eventually plunges her into a religious piety, one where she feels she must make sense of a world full of sin, even if that “devotion is conditional upon the continued gift of God's ecstasy.” However, while Laughton's film never questions the validity of the Reverend's conversations with God due to the human hypocrisy that lies at the heart of the character, the film and the examples listed here are just a few illustrations of the profound influence the character has had within religious horror.

In addition to the religious horror and hypocrisy as exemplified by villains like Harry Powell, The Night of the Hunter also frames said horror through the noir genre. In the film, Laughton posits the idea that monsters like Reverend Powell insert themselves within rural communities, using faith as a tool to deceive unsuspecting people. At the same time, these self-proclaimed righteous individuals commit actual sinful acts. A wolf in sheep's clothing if you will.

In effect, the film subverts the typical hopeful underpinnings that come with religion and instead positions it within a more cynical framework through the noir genre by looking at the detriment and horror that extreme religious views can have on a society. In David Fincher's Seven, its central serial killer argues that the violent religious-coded crimes are in part meant to shock a city out of its crushing apathy. As one of the rare religious horror noirs that doesn't explicitly feature supernatural elements, Fincher's film juxtaposes its violent religious acts with a nameless, crime-ridden urban sprawl that exudes hopelessness and cynicism in every frame, exemplifying the noir genre. In effect, both films are connected through the hypocritical religious violence perpetrated by their villains as a response to impart their twisted beliefs on the destitute environments around them.

On the other end of the religious horror noir spectrum, however, are the films that do frame explicit supernatural elements through noir trappings. Angel Heart follows a post-war gumshoe, Harry Angel (Mickey Rourke), tasked by an obviously named Louis Cyphre (Robert De Niro) to find Johnny Favorite, a singer who owes Cyphre an unspecified collateral. This classic noir set-up descends into the urban depravity of NYC, and the messy racial politics and voodoo occultism of New Orleans as Angel is forced to confront the darkness of both the world and his own soul.

Similarly, The Exorcist 3 uses an incredible George C. Scott to position the nature of God and vile murder in the world after discovering the death of a young Thomas Kintry: “The whole world is a homicide victim, Father. Would a God who is good invent something like that? Plainly speaking, it's a lousy idea. It's not popular. It's not a winner.” Blatty's film takes the darkness of unfathomable, violent acts perpetrated by a supernaturally revived Gemini Killer (Brad Douriff) to test the elderly detective's resolve, which is marked by faithlessness and cynicism in a Godless world.

Returning to Constantine, entertainment critic Priscilla Page notes that the fatalism of noir is baked into the DNA of the film. Specifically, that of advertisements mocking the abandonment of people to the eternal game between Heaven and Hell when Constantine (Keanu Reeves) reads a sign that says: “Your Time is Running Out … To Buy a New Chevy,“ after his lung cancer diagnosis. All of the above listed examples are brief, yet fascinating patterns that have followed in the wake of Charles Laughton's seminal film. Yet, where his film centered on the very real dangers posed by men like Reverend Harry Powell, many films that have since been influenced by it have opted for a more supernatural approach in depicting the religious horror within a noir framework.

Ultimately, it is the combination of these elements that still makes The Night of the Hunter such a foundational film. Laughton's film exposes the deep hypocrisy that runs rampant in men like Mitchum's character, who employ violent religious rhetoric to impose their own beliefs upon the world. By framing religious horror through the noir genre, the film opens up a cynical approach to Christianity that has influenced many films since. They may add their own flavors to an extremely potent recipe, subverting expectations here and there, but the lessons and reach of Laughton's film at 70 years old still loom large today in the face of those who do not practice what they preach.