(Editor's note: Acclaimed novelist and comics writer Benjamin Percy (Detective Comics, X-Force, Wolverine) has chronicled the making of his new short film, and we're bringing you the saga in six parts as his short makes its online debut. It's a fascinating, detailed journey of interest to aspiring filmmakers and genre fans alike. We hope you enjoy the ride! )

———–

Maybe it had something to do with turning forty. With the age comes a bald recognition, knowing you might be more than halfway to the end. There’s a nagging reassessment too—as you look back on what you’ve done…and look ahead to what you want to do…before the incinerator reduces you to ash in an urn or the worms chew you down to dirt in a grave. We only have so much precious time to put our dent in the universe.

Or maybe it had something to do with the pandemic. I spend most of my working life in my basement office. The dungeon, I call it. Here I write for an average of eight to ten hours a day. I am grateful for this life—I remind myself of that every day when I sit down at the desk to hammer—but there is perhaps something unhealthy about spending so much time with your imaginary friends.

I became acutely aware of this during the Covid lockdowns. Collaboration appealed to me in a way it hadn’t before. Whether I was talking on the phone with a Marvel artist—or meeting over Zoom with a director about a TV pilot—I felt energized by the fact that we were all working strenuously to tell the best possible story. I wanted more of that.

Or maybe it had something to do my experience in Hollywood. I’m known more for my novels and comics, but I’ve been a card-carrying member of the WGA screenwriters guild since 2014. During that time I’ve been lucky enough to sell some pilots and features, and I’ve adapted some novels and short stories and articles (and even a video game) into scripts. I’ve even had a few things escape the fiery grip of development hell and get made.

No doubt you’ve heard this before, but I am here to tell you it’s true: the writer is the lowest rung on the ladder. I have many industry horror stories (a few of which concern real-life boogeyman), but my constant and greatest frustration is this: how much time is wasted chasing directors. A project only takes on a golden luster, seemingly, when a notable director is attached. So weeks become months. And months can become years.

Because once you finally find someone who’s interested, they have notes. Notes that take you weeks or months to implement. And then, once you hand it the fresh draft, there will be several more weeks or months for the director (and producers) to process the revision and respond. Oftentimes, somewhere in the middle of this process, the director bails, because they have another project shooting. The producers lose interest. The project dies. For the sake of control, but also efficiency, I wanted to take control of the reins.

Regardless of why, something was eminently clear to me: I would be disappointed in myself if I didn’t write and direct a horror film. I grew up on a steady diet of EC Comics, Stephen King, John Carpenter, and yes, FANGORIA magazine. I am hard-wired for revving chainsaws and howling werewolves. If your story involves a vampire tapping at a second-story window, a yellow-eyed demon geysering green vomit, a doll shoving someone down a staircase, or a masked terror sliding a butcher knife out of a drawer, you have had my rapt attention since I was five years old.

That was when—as a kindergartener at Crow Elementary in Oregon—I pulled off the library shelf a book about the Universal horror movies. I studied the black-and-white photos of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney, Jr., slipped the book under my shirt, and claimed it as my own. Even then I knew my company was best suited for monsters.

I can imagine no pursuit more thrilling—and no distinction greater—than horror movie director. That’s my ultimate dream (or maybe I should say nightmare). The fact that I’m only chasing this now isn’t because I’ve put it off. For me the timing feels exactly right. This experience, like everything else in my career as a storyteller, has been incremental. I started off writing short stories for literary journals. This opened the door to writing fiction and nonfiction for the big glossy magazines like Esquire and GQ.

Then came the novels, the comics, the audio dramas, tv, film. I’m fast-forwarding through many years of late nights and tossed drafts and a reeking, dripping garbage truck full of failure and rejection. What’s important to note here is, I think of each of these mediums as rungs on a ladder. I needed to find my purchase in one to work my way up to the next. And I think there’s something to be said about the slow but invaluable transition from novelist to comics writer to director.

A novelist is a world builder. Every job is yours to figure out. Production design, acting, wardrobe, makeup, special effects, mise en scene, even catering. The story succeeds or fails as a result of a solitary, methodical process that can take years. The thick, bristling forests of sentences bear very little resemblance to the spareness of a script, but the fully realized vision of a novel helps give you the confidence to request a wardrobe change, fight for a line of dialogue, and understand the motivations of every character. It is a vision that fills in the white space of a screenplay.

Novels are not a visual medium, but they unscroll in my head like a film reel. I’m able to bring these internal images more vividly to external life in my comics. Every issue is like a collection of the most interesting frames of a film scissored and taped together. My scripts describe each of these panel-by-panel “shots,” along with the narration captions and dialogue balloons.

I then serve as a kind of team leader. I work on the one side with the penciller and inker and colorist, approving costumes and locations, signing off on layouts. But I’m also simultaneously in discussions with editorial, legal, and marketing, pitching proposals for future storylines, negotiating crossovers with other series, arguing about the rating system, and doing press with magazines and podcasts. Each issue is a like launching a film in miniature (with an unlimited special effects budget). But the process is a constant sprint, as I’m often handing in a script or two a week, juggling multiple titles.

All of this felt like a slow apprenticeship. So did the visits I made to sets over the years. And the time I spent observing audition tapes and popping in to editing bays. And the access I had to actors and sound design on the audio dramas. But I knew I had a hell of a lot to learn before I took on a budgeted film project. That’s what this series of essays is about. The hell of a lot I learned about making my first horror short. I never went to film school, but this always humbling, often inspiring, and occasionally frustrating education that spanned most of the last year turned out to be the next best thing.

The Idea

Because I write horror, people often ask what scares me. I have my jokey answers. Like dentists. And clowns. And sharks. And dentist clown sharks. But here’s the devil’s honest truth. The only thing that truly scares me—that curdles my marrow and makes me sweat poison—is something terrible happening to my kids. Want to hear a horror story? A real one.

When my son was an infant and toddler, he had trouble with his breathing due to underdeveloped airways. Several times every winter, he would get croup and his throat would swell and his breath would sound like someone trying to suck wet gravel through a straw. Here is one of my worst memories. He is ten months old. I am watching him hoisted on a stretcher into the back of an ambulance. His face is turning blue from a lack of oxygen. The doors close. The siren wails. The lights flash. And I have to follow him—in my own car, through a blizzard—not knowing whether he’ll be intubated or even alive by the time we reach the hospital.

Spoiler alert: he’s okay. He outgrew the condition and he’s now an obnoxious teenager with a Letterboxd queue stacked with horror films. But to this day, if I hear him coughing, my nerves tangle into barbed wire. That’s the good stuff, if you’re a storyteller. Traumas. Tragedies. Anxieties. The raw, true material that can become something powerful on the page and screen. If I felt that deep, awful terror myself, I might be able to infect you with the same. So that’s where I went for this project. I set out to write a story about a parent who will do anything to keep his kid safe. Anything. Because I would have.

I have a habit of being overly ambitious. In the first comics pitch I ever wrote, I proposed a thirty-issue horror epic. In the first feature spec I wrote, I plotted out a nightmarish takeover of an airport that probably would have cost $300 million. Both ideas were instantly rejected by everyone. You think I would have learned my lesson. I hammered out a script for a short film called Ward. I had been thinking so hard about the high-concept idea, the spooky atmosphere, the plot twists, the emotional arcs of the characters…that I kind of, sort of forgot about the budget. It was only going to be fifteen minutes? Surely that wouldn’t cost too much.

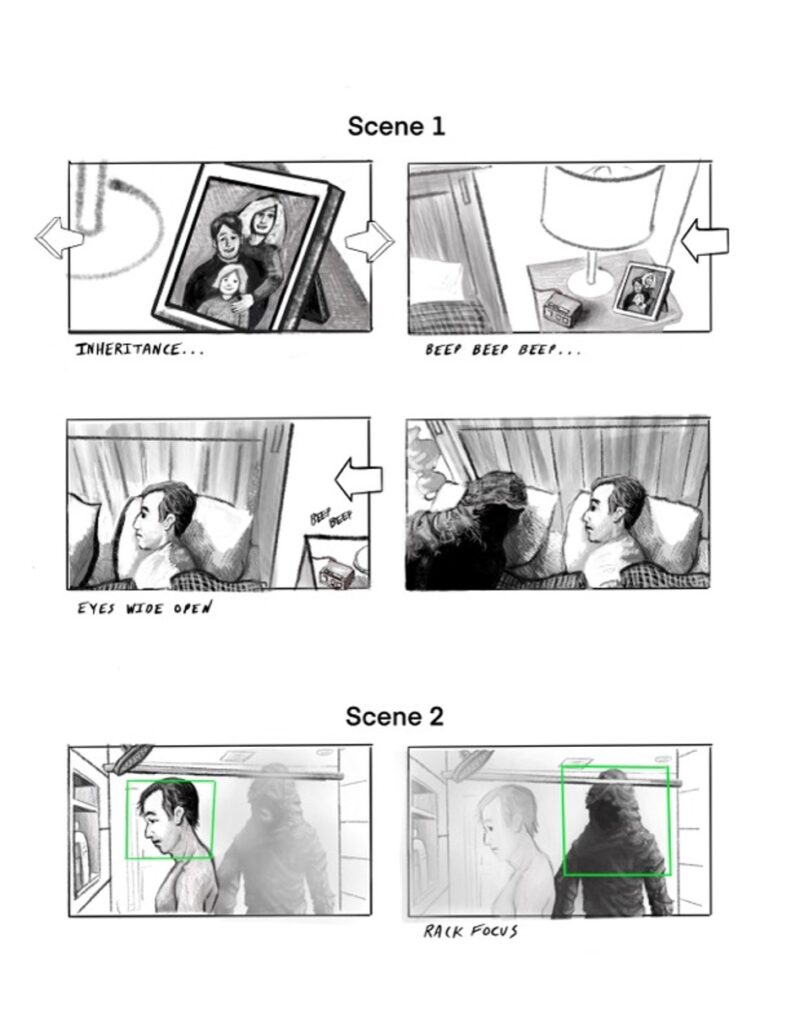

I sat down with a friend of mine, Matt Bowers, who is one of those rare freaks who is good at everything. A Swiss Army knife of a human being. Among his many talents: he’s a fantastic artist. I bribed him with a six-pack and he generously worked with me on some creature designs and storyboards. It was a struggle to get him to simplify the style and detail, because he was ready to go full graphic novel on me.

I hoped to use these as part of a package. I had no experience as a director, so I had to prove I was up to the task. To producers, to a D.P., to actors. If I was going to convince people to join me—on a project that promised more artistic than financial reward—I needed to get them geeked about joining forces. That meant I needed to prove I had a vision worth committing to, while also openly seeking their feedback and collaborative energy.

When I reached out to a producer I know, I received some ugly news. She loved the script. But she broke down the budget, and it was going to cost $77k. I was floored and disappointed. I got a second opinion and then a third. Fifty-six thousand was the lowest anyone could possibly imagine Ward costing. I had a creature (budgeted at $10k alone). I had a car striking a bicyclist. I had cops and EMTs at the scene of the accident. I had several sequences in a hospital. I had some gross-out special effects (including a body that gets annihilated in an OR so badly that blood drips from the ceiling and oozes down the walls).

The producers talked to me about grants and fiscal sponsorships, but I was opposed. That was a ridiculous amount of money, I felt, the kind you ought to spend on a first feature. Maybe some would disagree with me, but a budget of that size felt a betrayal of the spirit of the project. A short film is not supposed to be a gross expenditure. A short film is supposed to be scrappy. I needed to do more with less.

Creative restraint can be inspiring. I’ve learned this when writing for comics, a medium in which you don’t have twenty-one pages or eighteen pages—you have twenty pages. Exactly. And in those twenty pages, you have five to seven scenes, two splash pages, an A, B, C, and D plot, and a cliffhanger to get the nerds back to the shop next month. The poet Terrance Hayes says—when speaking about the difference between free verse and form poetry (like a sonnet or senstina)—that it’s cool if you can breakdance, but it’s badass if you can breakdance in a straitjacket.

Writing for comics feels like breakdancing in a straitjacket. Making a short film should feel like breakdancing in a straitjacket too. I didn’t toss out Ward. I converted it to a short story that I published in a speculative journal called F(r)iction . And then I thought about some of its core themes and how I could simplify the plot that contained them…and I started over.

Education

I did all the obvious things. I bought several books on directing and pawed through them, making notes in the margins, feathering chapters with sticky notes. I watched StudioBinder videos on YouTube. I signed up for a production class and an audio class at a local non-profit arts organization called FilmNorth. And I asked folks for advice. Producers. Directors. Showrunners. Film festival organizers. I’d get on the phone or on zoom. Or I’d offer to buy them coffee or a meal. And I’d pick their brain. But this was all theory, and I knew what I really needed was practice. A hands-on experience.

I live in the woods—but three or four times a year I travel to New York City for events or meetings. The first hour of every visit feels like an assault on the senses. The grinding traffic, the clogged sidewalks. Neon glows. A cab honks. Steam rises from a grate and a pile of hot garbage gives off a wave of stink. A man yells into a cell phone. A subway rumbles beneath a sidewalk and a siren howls through the canyons of steel and glass.

I’m trying to take all of this in while my brain flashes a warning: does not compute, does not compute. But then, gradually, I settle into the rhythm and noise of it all, and I’m just another jaywalker dodging between town cars and bicycle deliverymen.

I recognized that going from hermetic writer to multi-tasking director might feel similarly frantic. To ease the transition, before taking on a budgeted project, I decided to direct something simple and low-stakes. A zero-dollar, seven-hour shoot. This was Author. In a way it was an utter rejection of that $77k budget. I wanted to see the most I could accomplish with the fewest number of resources. The shoot would take place almost entirely at my house and in the woods out back. There would be two characters, and a three- person crew, all of them pals.

The found-footage story involved a podcaster and YouTuber who tracks down a reclusive horror author for an interview. Things go from weird to worse. For the shoot, I filled an entire closet with sticks and vines—a set we referred to as the root room. A hunter I know donated a deer heart from his freezer. I sent out an email to the neighbors, warning them about the shoot and kindly requesting that they not call the cops if they woke up late at night to screaming.

We braved nettles and mosquitoes. We skipped makeup. We shot on iPhones and borrowed the sound and lighting equipment from a nearby university. I ended up slathering my friend in fake blood—in the middle of the woods in the middle of the night—while he stood there in his tighty whities and said, “Better splash some more on my junk.”

Okay, so maybe it wasn’t a zero-dollar shoot. I had to buy the fake blood. And everyone in the business says the same thing: don’t skimp on food. So pizzas and a charcuterie board and a veggie tray kept people fat and happy until we wrapped around 2 AM. From start to finish, Author exceeded my expectations. The shoot was a total joy. The post-production process was a fascinating puzzle. Maybe the short wasn’t good enough for the festival circuit, but the experience itself was a shot of confidence to the jugular. I felt energized, more eager than ever to take that next step.

13th Night

I had learned my lesson with “Ward.” Forget the car crashes and hospitals and creature effects. I needed to shrink down the budget and the perspective. The heart of the narrative remained the same—a parent wanting to protect their kid—but this would play out in a fishbowl environment. So here’s the story I dreamed up.

Once a month, a man named Jacob has to kill. He does so with sickening reluctance, but has no choice. His daughter is desperately ill. And Jacob has a made a deal. A deal with a specter of Death—known only as The Agent—who visits him on the 13 th of every month. As long as Jacob delivers on his kill list, his daughter will continue to live. But he’s reached his breaking point—and he wants to negotiate a new contract. This is 13th Night.

No matter how cool your conceit—whether it involves a vampire train, squid aliens, or time travel—the audience won’t give a damn unless there’s a beating heart at the center of your story. I not only needed a great character in Jacob—I needed a great actor.

So I wrote with one in mind. I’ve been friends with Benjamin Busch for close to a decade. He’s a writer, a musician, a painter, a director, and an actor (known for his roles in The Wire and Generation Kill). He’s also a decorated veteran. Jacob would be a weary warrior—and I knew I could find that in the spirit and physicality of Busch. He also lives in nearby Michigan, and I knew he’d be generous enough (with the friendly bastard discount) to join forces with me for SAG minimums.

The script opened with a brief scene in a wooded area, but otherwise took place entirely in and around a house. At a glance this is a simple decision, but there are a number of complicating factors I was trying to control. I wouldn’t be able to afford a producer, so I was going to have to handle all the logistics myself. A stable situation would free up my brain up so that I could concentrate on the actors.

The parking, prop room, makeup room, catering area, and bathroom would all be easily accessible—and the same every day. And, critically, I could control the light. The opening scene would happen outside at sunset. The rest of the story would take place not just in a house, but in a house that was in a state of lockdown—with curtains pulled and the doors locked—so that I could black everything out. We could shoot something at 10AM or 7PM and make it look the same.

As for my monster, I knew I needed to apply this same stripped-down sensibility. Earlier conversations had made it clear I couldn’t afford a creature. So I thought of some of the human baddies who haunted me through the years. Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs, Kane in Poltergeist II, the Tall Man in Phantasm, the Mystery Man in Lost Highway. I blendered them together in my imagination when writing. Normally these sorts of restrictive decisions don’t drive my creative process, but as the writer and director, I was using both sides of my brain at once. And that’s how I built the script for 13th Night. I had my fifteen-page script. Now I just needed…

Money

A friend of mine, who owns a restaurant, once said to me, “You have no overhead. I can’t think of another job like that. It honestly kind of pisses me off.” As a writer, I don’t have to order napkins or dishes or butter or lettuce, in other words. Outside of a laptop, all it takes to write is a demented imagination and a bottomless urn of coffee. Not so for a film.

I could call in some favors, but if I was going to level up, I needed to hire a crew and I needed them to feel fairly compensated for their time. I needed money. So I applied for a fellowship—through the McKnight Foundation here in Minnesota—and included a script for 13th Night, a game plan for getting it made, and an impassioned plea that imparted my dream of becoming a horror film director. Amazingly, thankfully, I won.

The situation suddenly became real and urgent. I was no longer talking about making a movie. It was happening. And prep began immediately.

Continued tomorrow in Part 2!