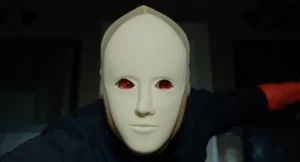

Fixated on avenging her late husband, a widow infiltrates and destabilizes a sweet all-American family from within by adopting the gentlest and thus most persuasive of disguises — that of a children’s nanny. She subtly and effectively undermines the wife, poisons the young daughter against her mother, and attempts to seduce the husband. Played with equal parts calculated charm and concealed menace by Rebecca De Mornay in the 1992 thriller, The Hand That Rocks The Cradle, this year’s remake finds indie horror icon Maika Monroe unspooling her own suburban nightmare.

“What do you know about her? Besides what she’s told you,” asks a character in the trailer, and what initially seems like a subversion of Monroe’s filmography — she’s our most compelling modern Final Girl, here playing the villain instead — now slots neatly alongside her career of playing characters who shrewdly weaponize our assumptions of them. Her horror heroines are often traumatized and tortured women from broken families, their perceived vulnerability making them the target of predatory, unscrupulous men (or in the case of 2022’s A Significant Other, even an otherworldly entity masquerading as one). They tend to underestimate her, and that’s their mistake.

See our The Hand That Rocks The Cradle interview with Maika Monroe and Mary Elizabeth Winstead here.

For all her characters tend to withdraw into themselves, succumbing to paralyzed fright rather than lashing out, they’re also defined by a quiet steeliness. Monroe’s is often a face that conveys shock, but also the simultaneous strain it takes to keep one’s composure anyway. Her largely internal performances make her either the most grounded character in a cast full of unhinged personalities, such as in Villains, or the sole glimpse of humanity in a sterile, AI-powered environment, as in Tau. All that fragility belies an understated fierceness that her characters have been drawing on since her breakthrough in 2014’s It Follows.

Monroe’s understated approach is crucial to a film like the twisty, shapeshifting sci-fi horror Significant Other. As Ruth, on a couple’s camping trip with her boyfriend Harry (Jake Lacy), the actress switches gears from stressed-out and dizzyingly panicked by a recent relationship upheaval to eerily placid after she stumbles into a cave containing crucial information the audience isn’t yet privy to.

When she apologizes for not “feeling like herself” later, her blank face and monotone intonation conversely convey the tremendous restraint she must be employing to hold herself together. Her even-keeled acquiescence to Harry’s plans might seem like a massive underreaction to the cataclysmic revelation she’s confronted with, but her performance resembles that of every woman attempting to placate and defuse a potentially violent man. She doesn’t have the luxury of an outburst because she can’t afford to give herself away. This is Monroe delivering a precisely calibrated performance as Ruth calibrates hers.

Such disciplined control is also what saves another Monroe character, former actress Julia, in the Hitchcockian thriller Watcher. Monroe deploys her innate stillness to duplicitous effect, leading the serial killer who’s captured Julia to assume she’s dead, only for her to swiftly and unexpectedly make him the victim instead. Watcher makes for a great double bill with the eerie, atmospheric psychological thriller It Follows, both films about the paranoia of being watched.

Like Watcher, it emphasizes its protagonist’s loss of control, which Monroe captures through the frozen fright that permeates one desperate sexual encounter and a detached numbness in the aftermath of a second offscreen one — her character can only escape being stalked by a malevolent entity if she ‘transmits’ it to another person.

In Watcher, this helplessness manifests as her wandering around, unmoored, through Bucharest. Having moved there for her husband’s (Karl Glusman) new job, she knows only a few Romanian phrases, which she speaks haltingly. By excluding subtitles for conversations in the language, the film renders us as isolated as Julia feels. Sweet and overly accommodating, she shakes her head while describing how she was followed, if subconsciously dismissing her experiences before her husband can. “You think I’m crazy?” she asks. Monroe’s voice is hurt, almost pleading, when he tries to rationalize away the incident.

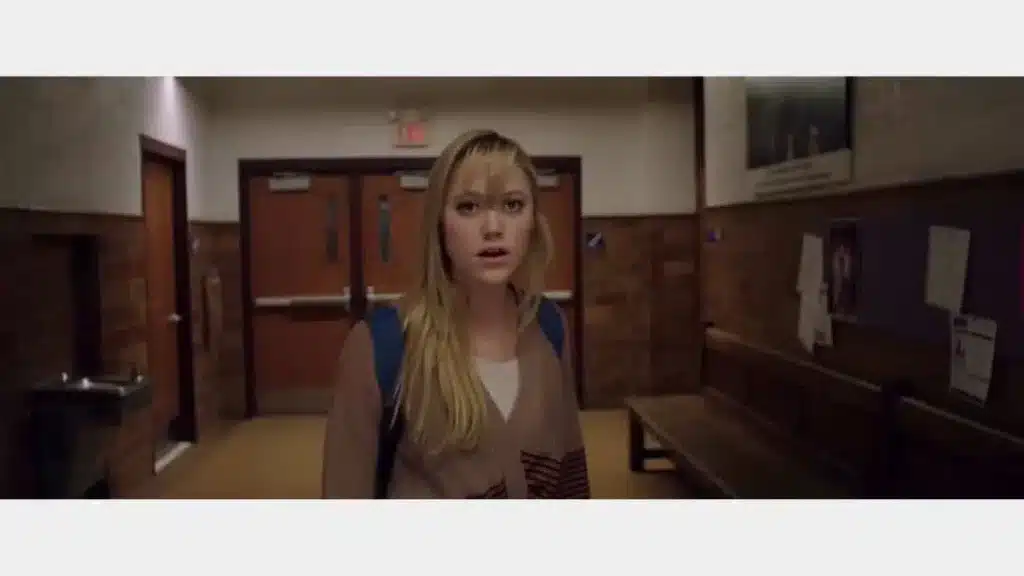

But if one woman is all too aware of the threats men pose and perpetuate, the other remains naive. When It Follows’ Jay Height awakes to find herself bound by her boyfriend, who passes the stalking homicidal entity onto her in the first place, her reflex isn’t to panic. Instead, she plaintively asks what’s going on. Monroe imbues her with a childlike innocence, the film underscoring this through childhood photos or imagery of her wrapped in a blanket. Slowly, however, traces of the subdued young girl disappear, Jay’s voice rising in tandem with her panic.

One of the actress’ earliest Final Girl films also honed in on her youth and inexperience, contrasting it with a wise-beyond-her-years rationality. The Guest’s Anna Peterson is 20 but appears much younger, embodying the moodiness of an unruly teen, but also appearing uniquely sensitive to her parents’ grief after the loss of their older son. She’s sarcastic and poker faced, but Monroe frames these as defense mechanisms, a front for her character’s pain.

When Army sergeant David Collins (Dan Stevens) appears at her family’s doorstep, claiming to be her late brother’s best friend, Anna succumbs to his charm and flattery — as does almost every other character in the film — but also proves to be adept at seeing through its falseness.

After a series of killings ripple through the town around the time David appears, it’s not the steely and in-charge Army major (Lance Reddick) intent on taking him down who ultimately survives the film, but her. When she pulls the trigger in self-defense, she instinctively drops her hands and looks away, as though to distance herself from her actions in disbelief — she can’t believe what she’s capable of either.

Victim-captor dynamics are similarly flipped in Greta, a psychological thriller in which unstable widow Greta Hideg (Isabelle Huppert) forms a suffocating attachment to young waitress Frances McCullen (Chloë Grace Moretz). As the wealthy Erica Penn, Monroe plays not the beleaguered Final Girl, but her best friend and voice of reason instead. She’s unbothered enough that when she thinks Greta might be stalking her too, she still leaves the bar she’s at alone, heading out the back through a dark alleyway, more annoyed than afraid, only for strutting to turn to sprinting soon enough.

Monroe’s performance forms the cool, collected counterpoint to Moretz’s hysteria and Huppert’s histrionics. When Erica eventually wrests away control from Greta, outplaying her at her own game, she doesn’t gloat. Instead, her tone is solicitous, her smile sweet, which makes the schadenfreude so much more gratifying.

Monroe’s gas-station robber in Villains has more fight than her other characters, but these wild swings are often painted as the deluded confidence of someone who can’t win, or has messed up drastically. It’s her quieter moments that lend emotional gravitas to this freewheeling horror comedy about two amateur thieves who break into a remote house and discover themselves up against its unnervingly odd inhabitants.

As Jules, Monroe’s voice softens as she loses herself in the memory of her parents abandoning her as a child. She processes a climactic death not with an overt outburst but with a shattering despair and moving tenderness for the departed, lending the film a sadness that contrasts with all the kooky hijinks that have come before.

“I’ve got to come up with hope and sadness and fear, and the whole time I’m talking to a wall,” Monroe said of her performance in sci-fi thriller Tau, in which her character is abducted by a sadistic tech genius (Ed Skrein) and held hostage in his AI-run smart house. “We didn’t even have [the AI’s] dialogue recorded [by Gary Oldman] because they shot my scenes first and then used those to direct his voice work.”

She spends the initial stretches of the film muzzled, conveying pain, panic, and confusion solely through her eyes. Her performance speaks to her knack for reacting to the atmospheric unease of an empty space just as easily as she would a tangible scene partner. She does so in Watcher and the procedural horror Longlegs, too.

In Osgood Perkins’ horror movie, a young girl asks Monroe’s character if it’s “scary being a lady FBI agent.” What she doesn’t know is that Lee Harker’s life has been molded by horrors well beyond the scope of her job, right from childhood, by the devil himself. Her sentences are short and to the point; she whispers as though suffocating.

Monroe plays Lee with her signature evasion of eye contact, but here, the “highly intuitive” agent sees what others can’t, holding herself as though attuned to a different frequency. Tightly wound and skittish, she radiates unease. She’s not at home in her body; her mind is somewhere else. Monroe’s measured performance charts a character coming undone as her repressed trauma gradually begins pouring out through the cracks. When unwelcome memories intrude, Lee recoils as though shoved back with the force.

“I think back to some of the horror movies I would watch [as a kid] and it would be hot, blonde girls with half their clothes falling off covered in blood and running and screaming,” the actress said in an interview. Screams are rare in Monroe’s horror filmography, though often primal and cathartic. Her talent instead lies in using repression as a means of revelation. In Significant Other, a late twist reveals the actress in a double role, the imitator realizing it can’t possibly embody the real deal. It’s a fitting metaphor for a Final Girl whose craft is singular.