Mexican writer/director Isaac Ezban has explored many areas of horror and science fiction over the course of his career, from the Twilight Zone-esque The Incident and The Similars, to the multiverse-tripping Parallels, to the folk horror of Evil Eye. Now, with Párvulos: Children of the Apocalypse, he dives into the postapocalyptic-survival subgenre for arguably his most gripping and bleakest film yet.

A Firebook Entertainment release (opening in select theaters April 4; tickets can be purchased here) that has won numerous festival awards, Párvulos is set in the aftermath of a plague that has wiped out most of humanity. Among the few survivors are three brothers: teenage Salvador (Felix Farid Escalante) and the younger Oliver (Leonardo Cervantes) and Benjamin (Mateo Ortega).

They’ve managed to successfully fend for themselves by keeping to established rules and routines, and avoiding the danger that lurks in the surrounding woods. When a woman named Valeria (Clara Adell) arrives, she represents a potential mother figure for the boys, and more for Salvador—but can she be trusted? And what’s the secret the siblings are hiding in the basement, which is revealed around the halfway mark? (We’ll only discuss that crucial element beginning midway through this article.)

Párvulos, for which Ezban and Ricardo Aguado-Fentanes came up with the story, was sparked by the director’s desire to create a combination fright film/coming-of-age story in the tradition of Stephen King and Guillermo del Toro. He sees it as the second in a planned trilogy that began with the female-driven Evil Eye. FANGORIA spoke to Ezban following Párvulos’ world premiere at 2024’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

There’s been a kind of mini-trend in genre cinema over the last decade or so involving parents, or parental figures like Salvador, protecting children against the horrors of the outside world. Why do you think that has become such a concern?

I feel that’s something very universal. We’ve seen stories about that not only in the last decade, but overall in the history of horror. Why do horror movies always deal with families, something happening to a child, a child being possessed, a family arriving at a new house or getting lost? Because it’s something we can all relate to. Horror has to be very human. Even if there are monsters and all that, it has to have a very human connotation. If that isn’t present, there’s nothing we can identify with. Horror can always serve as a metaphor for something else, and what is the biggest fear somebody could have? The fear of something happening to their family.

Can you talk about casting the kids, and finding good young actors who also had the right chemistry as brothers?

In making a movie with children, casting is 50 percent, or perhaps even more. We opened up that process a few times, because we were going to make the movie a couple of times before, and it didn’t happen. And this time, when we opened it in 2022 to shoot in 2023, we looked at many different kids of many different ages.

The toughest part was finding the right actor for Salvador, because his role carries a lot of strength; he’s an authoritarian figure, and he yells a lot. Originally, I wanted a younger boy for that role, like 13 or 14, who would be only slightly older than the other two. You can imagine how the scene with Valeria in the bedroom would play completely differently like that, with a 13- or 14-year-old and a 26-year-old woman.

But it was very hard to find a boy that age who could pull off the authoritarian part and the way he yells and all that. With all the kids who did that, it just seemed fake, like they were playing. So my casting director, Rocío Belmont, who’s really good, asked me, “Why don’t we aim for a higher age for that role?” I was like, “No, no, no, I want this little kid with this woman,” and she was like, “Isaac, think about the entire film, not just that scene.”

So then we found Felix, who is a fantastic actor, and could do a lot of very physical stuff that I couldn’t do myself. So directing is all about making choices. I had to decide to sacrifice the contrast of age in that particular bedroom scene–which still works fine with Felix–in order to gain a better actor for the rest of the movie, which was obviously more important.

Were there any situations where the parents of potential young actors had a problem with the violence, etc. in the film?

We knew it was very sensitive, the things that happen throughout the movie. The kids had to be fighting, holding guns, killing a person, being choked by someone and all that, and we handled everything with a lot of responsibility, a lot of professionalism. We had the stunt coordinator rehearse all the fights with the kids, and we had a great acting coach, Ana Carrillo, who focused only on the children, on rehearsing with them, on getting them to the right emotions.

So the parents were actually very pleased, because they saw that their kids were happy. They were like, “Oh, it’s almost like taking them on a field trip.” One mother saw how her kid was getting thrown, but landed on a mattress, and she said, “I want to be a stunt double myself!” It’s important when you’re making a movie that is all about kids that you make them feel comfortable, and the parents feel comfortable.

(And now, the SPOILERS begin…)

How about casting the zombie parents?

I’m glad you asked about that, because a lot of people don’t even consider that—not because they don’t like their acting, but because they did so great that people just see them as part of the movie. I asked somebody, “Oh, what about the parents, they’re great!” And they said, “I hadn’t even thought about them as actors, I just thought of them as creatures.” That was very physically based casting, because they were very physically based roles.

We were very lucky to find Norma Flores, who plays the mother, because she was a model and also a movement teacher in acting schools. We needed somebody very thin, who had very short hair, so she wouldn’t mind chopping all her hair off for the movie, and she loved that. And then Horacio F. Lazo, who plays the father, was an actor I chose because I really liked his expressions and the faces he could make.

I believe they embodied the zombies differently. Norma doesn’t play Mama like a zombie, but more like an amphibious, reptilian creature with more flexibility, while Horacio played Papa like a classic ghoul from Romero’s movies. When I saw that’s how they were approaching their roles, I decided to use that in the film’s favor and play up the contrast between them, which I feel really works.

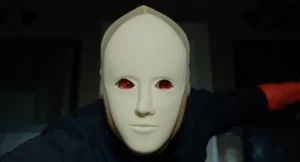

Who created your makeup effects, and how did you arrive at the specific look for the zombies?

Those were done by Roberto Ortiz, who is Mexico’s best prosthetics and makeup effects guy. If you saw Roma, he did the baby in the birth scene. He makes such amazing, cool stuff, and he started working on Párvulos a while ago. We did concept art of how the zombies would look, based on research on eating disorders and how that looks when people are very thin. Then we did a lot of tests with the actors, and Roberto was very much involved in choosing them. He came to the casting sessions and would tell me, “I like the body of this woman, the body of that guy.”

The makeup on the parents was a big deal, because it took three hours to apply and then four and a half hours to remove. So it was crazy; sometimes we had to begin the day at 7 a.m., put the kids in makeup, start shooting with them at 8 or 8:30, and then I didn’t have the parents all set until 12 or 1 p.m., since it took all that time to do their makeup.

The only real problem was when we shot all the basement stuff, because we worked just there for an entire week, since it was a separate location. And that involved the fully made-up parents the whole time; I could spend about 30 minutes shooting the close-ups of the kids, and that was it. Then the parents needed to play the whole day. So for that week, they were the first ones to arrive and the last ones to leave, but they did it very, very graciously.