“Are you saying the murders were committed by a supernatural creature?” Jeannie Anderson asks private investigator Holly Gibney in Stephen King's 2018 novel The Outsider. “Something like a vampire?”

The murders Jeannie is referring to are a string of depraved and brutal slayings that her husband, Detective Ralph Anderson, has the displeasure of investigating. And the supernatural creature—the “vampire”—is of a species that has appeared multiple times in King's work, both within The Outsider's extended universe and beyond. It goes by many names and wears many faces, but I believe Jeannie was fumbling in the right linguistic direction. I've grown to think of it as a “dread vampire.”

The dread vampire is a kind of psychic vampire, though not of the Colin Robinson variety. It feasts on negative emotions, but its victims rarely escape with a mild need for a nap and a Gatorade. Most die in unimaginable agony, their misery and pain ingested instead of (or in addition to) their blood and flesh. And when the bodies are cold, the dread vampire often slurps up all the remnants of the ruined lives it has left in its wake.

These creatures aren't as common as some of King's favorite character archetypes—the writer, the recovering alcoholic, the child imbued with devastating psionic powers—but when they do show up, they make for some of the author's most unspeakably evil villains. A big part of that is their choice of victims. The dread vampire has a penchant for eating children.

Join me, fellow Constant Reader, as we track these foul creatures down through the caves, sewers, and caravans in which they hide to better understand them. Perhaps along the way, we can even uncover what King's dread vampires say about how we process inconceivable evil in our real world. But leave your stakes and crucifixes at home. They won't do you any good here.

-

Fear adds flavor to Pennywise's victims in It

The first time I encountered one of the creatures I've come to call the dread vampire, I was traversing the fictional town of Derry, Maine, in the pages of 1986's It. Something dressed as a clown was luring children into the sewers, tearing off their limbs and feasting on them. But It wasn't always a clown. Sometimes It was a werewolf, a mummy, a cackling witch. Whatever it took to terrify Its young victims, to season them with fear.

“It had always fed on children,” King explains to us. “Many adults could be used without knowing they had been used, and It had even fed on a few of the older ones over the years—adults had their own terrors, and their glands could be tapped, opened so that all the chemicals of fear flooded the body and salted the meat. But their fears were mostly too complex. The fears of children could often be summoned up in a single face.”

For Pennywise the killer clown, fear is flavoring. It will sometimes torment a child for weeks or even months before snatching them, making sure they're good and frightened before It chows down. As Tim Curry's Pennywise succinctly puts it in the 1990 miniseries adaptation of It, “You all taste so much better when you're afraid.”

It likely doesn't hurt that the pervasive atmosphere in Derry, a town where the murder rate is six times higher than that of any other town of comparable size in New England, is one of overt violence and indifferent cruelty.

“Children disappear unexplained and unfound at a rate of forty to sixty a year,” even outside of Pennywise's killing cycles, according to Derry's unofficial historian, Mike Hanlon. Adults seem to turn a blind eye, leaving the children alone in their misery and terror.

King describes Derry as “It's private game-preserve,” but perhaps it can more accurately be called a slow cooker. Pennywise's victims have been marinating their whole lives.

Grief tastes good to El Cuco in The Outsider

Negative emotions play a slightly different—though no less sinister—role in the aforementioned The Outsider. Rather than flavoring the meat of the main course, fear and misery serve as something of a dessert to this breed of dread vampire, which the characters name “El Cuco” after the child-eating boogeyman of Latin American folklore. “In the stories, El Cuco lives on blood and flesh, like a vampire, but I think this creature also feeds on bad feelings,” Holly Gibney explains. “Psychic blood, you could say.”

Like Pennywise, El Cuco prefers to eat children, later explaining itself by saying they are “the strongest, sweetest food” (there's also a disturbing sexual element to this creature's crimes, but let's not get into that here).

Unlike Pennywise, however, adults account for a large number of El Cuco's calories. That's because this monster commits its murders while wearing the faces of local men, then drinks in the pain and horror this causes for them, their families, and the community at large.

Unfortunately for Little League coach Terry Maitland, El Cuco is wearing him as a disguise as it slaughters 11-year-old Frankie Peterson, which doesn't bode well for Terry's future. “I'd be in the death house up in McAlester before the end of summer, and two years from now I'd be riding the needle,” Terry acknowledges, a fate that El Cuco would surely find delicious.

As it turns out, Terry doesn't live long enough to be executed. A chain reaction of misery is triggered by El Cuco's actions, leading Frankie Peterson's father to attempt suicide, his mother to die of a heart attack, and his distraught brother to shoot Terry to death on the steps of the courthouse before being gunned down himself. The horror. The taste.

“If there really was a monster that eats negative emotions, that would have been Thanksgiving dinner for it,” Detective Yune Sablo says of the ordeal at the courthouse. And throughout it all, El Cuco is lingering in the crowd, risking detection just to lick the plate clean.

It even visits Terry's children for a midnight snack. “He told your daughter he was glad she was unhappy and sad,” Holly notes to Terry's widow. “I believe that was the truth. I believe he was eating her sadness.”

Holly succeeds in killing El Cuco after tracking it back to the cave where it was transforming into another of the town's residents, already lining up its next meal. But it isn't long before she crosses paths with another of its kind.

Disaster is delicious for the Grief Eater in If It Bleeds

The Outsider's El Cuco might be a secretive creature, but the dread vampire in If It Bleeds (a short story from King's 2020 anthology of the same name) has no qualms about being seen.

Going by the name Chet Ondowsky (among others), it has built a long career as a local reporter, giving it an excuse to chase ambulances and show up at the scenes of tragedies. Once there, it seemingly doesn't need to physically eat and drink of the bodies to feel full. This dread vampire is all about the bad vibes.

“He always picks the ones who are most upset [to interview], the ones who were inside or lost friends who were,” says Brad Bell, grandson of Dan Bell, an ex-police sketch artist who has been tracking the creature's movements for years.

Holly understands why the creature would gravitate toward these witnesses. No self-respecting grief eater would settle for a salad when it could have a juicy steak.

The creature that calls itself Ondowsky initially appears harmless, if grotesque. “It lives off grief and pain, maybe not a nice thing, but not so different from maggots living off decaying flesh or buzzards and vultures living off roadkill,” Dan Bell explains.

He goes on to speculate that Ondowsky might be similar to a mosquito, able to scent blood on the wind. When the world delivers tragedy, Ondowsky is ready with a knife and fork.

However, Ondowsky eventually grows impatient waiting for its Postmates to arrive. Slipping into one of its other faces, it blows up a school and eagerly reports on the aftermath. “Now it is no longer content to live on the aftermath of tragedy, gobbling grief and pain before the blood dries,” Holly writes. “This time it brought the carnage, and if it gets away with it once, it will do it again. Next time, the death toll may be much higher.”

Of course, the intrepid private investigator stops this burgeoning killer before it can put its next meal in the oven. But as the Constant Reader and Holly herself have learned, when one dread vampire falls, there's always another ready to take its place at the dinner table.

Sometimes, there's even a whole nest of them.

Pain purifies the True Knot's provisions in Doctor Sleep

While most of King's dread vampires hunt and eat alone, 2013's Doctor Sleep, the decades-later sequel to The Shining, introduces a whole cult of these creatures. Called the True Knot, this nomadic group is obsessed with identifying people who possess psychic abilities—people who “shine”—and ingesting the “steam” (psychic essence) they release when they die.

Similar to If It Bleeds, these deaths can sometimes happen without the True Knot's intervention. We're told that on September 11, 2001, the cult drove to New Jersey and passed around a pair of binoculars to watch the tragedy unfolding across the Hudson.

“There had been plenty for everybody that day, and in the days following,” the author explains. “There might only have been a couple of true steamheads among those who died when the Towers fell, but when the disaster was big enough, agony and violent death had an enriching quality.”

With its “limited precognitive skills,” the True Knot can sense major disasters on the horizon, but these are few and far between. Instead, the cult focuses its energy on tracking and murdering its prey. “[The True Knot] weren't vampires from one of those old Hammer horror pictures,” we're told, “but they still needed to eat.” And like Pennywise and El Cuco before them, this band of dread vampires prefers to eat kids.

Also, like Pennywise, the True Knot tends to play with its food. The cult tortures its victims extensively before murdering them because “agony and violent death had an enriching quality.”

This is exemplified in the novel's most shocking scene, where members of the True Knot lure an 11-year-old boy named Bradley Trevor into their van, drive him to an abandoned power plant, and torture him to death.

They torture Bradley for so long that his vocal cords rupture from screaming—so horrifically that he eventually begs for death. And throughout it all, they feel no shred of remorse.

“It was regrettable,” the novel notes, “but pain purified steam, and the True had to eat. Lobsters also felt pain when they were dropped into pots of boiling water, but that didn't stop the rubes from doing it. Food was food, and survival was survival.”

Is it, though? True Knot member Snakebite Andi certainly believes so, telling all-grown-up Dan Torrance that “we didn't choose to be what we are any more than you did.” But this is a lie: we witnessed Andi herself choosing to join the True Knot and being transformed into a steam-eating monster.

The tribe's members were human—they only began to “eat screams and drink pain” because it allowed them to “live long, stay young, and eat well.” Hannibal Lecter could just as convincingly argue that he had no choice but to do a little cannibalism because he was hungry.

There were other options on the table. The True Knot chose the unthinkable.

"They walk among us… Monsters beyond our understanding"

Much like his psychic children, King's dread vampires are all a little different. But beyond their predilection for misery, there's one thing they all share in common, and that's echoes of real-world serial killers.

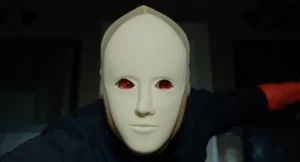

Pennywise has killing cycles and cooling-off periods. El Cuco and Chet Ondowsky enjoy returning to the scene of the crime. Even the True Knot, the most human of the bunch, feel no empathy for their victims. Rose Ferguson, who plays the cult's leader, Rose the Hat, in the 2019 adaptation of Doctor Sleep admits that she watched interviews with real serial killers in preparation for the role.

It's no surprise, then, that Holly Gibney directly compares one of these creatures to Ted Bundy in The Outsider, adding: “There are others. They walk among us… They're aliens. Monsters beyond our understanding.” She is referring to the human monsters that Detective Ralph Anderson hunts, noting “You've put some of them away, maybe seen them executed.”

For most of us, it's impossible to truly wrap our heads around how a person could commit the kinds of acts that Bundy did, let alone El Cuco or its kind. “Suppose it had been Terry Maitland who killed that child,” Holly says to Ralph when he struggles to accept her theories about a shape-shifting grief eater. “Would that be any less inexplicable… Would you be able to say, ‘I understand the darkness and evil that was hiding behind the mask of the boys' athletic coach and good community citizen. I know exactly what made him do it'?”

“I've never understood,” Ralph admits. “Most times they don't understand themselves.”

The monsters the detective is used to hunting may not understand what drives them to such obscene acts, but King's dread vampires do. That's what makes them so frightening. King poses the most horrifying answer possible to that eternal question: “What could make someone do such a thing?”

They did it because they wanted to.

Because it tasted good.