We needed locks. Lots of them. Pull chains. Sliding bolts. Twisting deadbolts. Latches with padlocks on them. Because we were going to include this killer shot—a shot that tilted down as lock after lock after lock after lock was engaged—driving home the extreme paranoia and danger of this night, the thirteenth night of the month from which the short film got its title.

But the house we were shooting in was a donated AirBnB. We couldn’t simply screw all that steel into the door and frame. We had to figure out a way to make it work, and it was 6AM on the first day of production…

Before I get into that, let me tell you more about Benjamin Busch. He’s a real-life warrior. You can read about his time as a Marine in his excellent memoir, Dust to Dust. That’s one of the reasons I asked him to play Jacob. Because he has the fierce wisdom and physical power to authenticate the role. And it doesn’t hurt that he looks the part. His face is as etched and sharp as an old hatchet. His arms are like the knotty trunks of trees. He’s tall and broad-shouldered and has grown out his hair in a heavy metal mane. He’s the sort of guy who can survive on a hunk of beef jerky and a thimble of snail slime for a month. He’s also the sort of actor who will drive 600 miles in one day, stopping only to fill up on gas and visit an army surplus store to see if they have any more weapons to add to the stockpile he brought along. He arrived in town, almost to the minute, when he said he would.

I’m a rookie director, and I wasn’t going to pretend any differently. Busch had a war chest of experience as an actor, writer, and director. He had spent five years working on one of my favorite shows of all time, HBO’s The Wire. I told him to be patient with me and to not hold back on correcting any mistakes or offering up any tips. I might viciously guard the words of my novels and short stories, but I knew I needed to take a more flexible, collaborative approach to my script. He made several smart suggestions for the dialogue that we incorporated. And he also had some ideas for dramaturgy.

He isn’t the type to dress up the delivery of bad news. When he called me, a few weeks before the shoot, he got right to it. “Your idea for this scene isn’t going to work.”

He was talking about the home invasion. As night fell, I had Jacob fortifying his home, readying for an attack. He locked the windows, closed the curtains. Braced doors. Readied weapons. And then, the cherry on the sundae, he fitted several lightbulbs into a tube sock, crushed them with a hammer, and sprinkled the glass throughout the foyer.

Jacob was going to sit in a chair, a machete in his lap, waiting for the arrival of his enemy. But whiskey and exhaustion would catch up with him, and he would nod off. The crunch-crinch of broken glass would wake him. He would creep toward the foyer and discover the door open and bloody footsteps leading across the hardwood.

“Here’s what you’re not thinking about,” he said. “Problem number one. The hardwood itself. It’s old, so the lacquer might be worn. Wood’s porous. The fake blood might make a permanent stain, and then you’re on the hook for several thousand, refinishing the floor for the owners of the house.”

“Noted,” I said, still not convinced.

“Problem number two. Makeup.” Later in the script, when Jacob’s daughter hears voices and gets out of bed and finds her father, she says, “You’re bleeding.” He looks down and discovers his feet are shredded from the glass. The bloody footprints he saw earlier were his own, driving home the possibility that the Agent is a threat that exists only in his head.

“When my feet are bloody and cut up—that’s going to take an hour or two to set up. You really want me lounging around, getting latex wounds applied to the soles of my feet for that long? And then afterwards, we’ll have to get me cleaned up. We’ve only got three days. The clock’s ticking. No time to waste.”

That did the job. I was convinced. But I needed something to replace what we were cutting. To do that, I had to focus on what the scene was meant to accomplish. I wanted to illustrate the agent’s power, the impossibility of stopping him, no matter how strong the defenses Jacob erected.

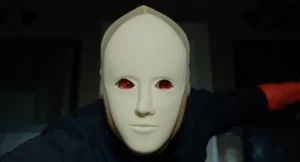

Here’s how the revision turned out. When Jacob awoke in his chair, when he heard the sound of someone trying to get inside, when he stalked toward the entryway, he would find the door (and its locks) gone entirely. He would stare deeply into the vacant rectangle, studying the night, waiting for something to rush out of the darkness. Then a sound would assault him—the rattle and clank of metal—from inside the house. He would pivot away from the open doorway and toward the dining area. Here we would find the Agent, grinning widely, dropping locks and hinges onto the tabletop.

This pivot made so much sense—it avoided the slow inconvenience of makeup and it efficiently underscored the power of the Agent.

But we still needed those locks, and it was 6AM on the first day of production. Busch had pitched me the idea of two steel plates. One on the door, one on the frame. They would be an inch or so thick and mounted with gorilla tape. Onto these we would screw the locks and bolts and chains and their casements.

He had brought along he materials and showed them to the production team and assumed they would know how to cobble it all together. But after sitting in the makeup chair for a half hour, the job still wasn’t done, so he marched out to the garage and busted out his hammer, saw, and drill. In fifteen minutes, we had the fake locks mounted, seemingly capable of keeping out even a demon with a battering ram.

I share this story for a few reasons.

The first is, the willingness and flexibility to pivot. I’ve come to recognize that everyone involved in a film project has the same title: storyteller. We just all specialize in different things. Probably the most destructive thing you could do as a director is think that you’re the ultimate voice and vision for a project. Listening to Busch and finding a new way forward was the best thing I could have possibly done.

It’s also a moment that illustrates how, no matter how much time you put into prep, there’s always going to be some last-minute chaos that needs to be settled before the camera rolls. We didn’t have a key prop built or tested until the morning of the shoot. This made me want to grind my teeth down to powder, but it all worked out.

And it all worked out, because Benjamin Busch embodies the collaborative spirit of short filmmaking. He was there to act, but he served as a production designer and stunt coordinator and prop supplier and script consultant (and and and…). He brought a van packed with weapons and costumes and mirrors and paintings that would populate the backgrounds. If you’re going to make your first short, my advice is to find yourself a Benjamin Busch.

Find your people, in other words.

One of the DPs I spoke to said he was tired of the late nights and hard work. One of the sound mixers I spoke to said he was not interested in anything that resembled “guerilla filmmaking.” I understood where they were coming from—and I also understood that they weren’t going to be the right allies in the scrappy battle to get this short made.

War Room

In the basement of the house, there was a wide-open room with a ping-pong table in it. On the ping-pong table, I laid down strips of masking tape and labeled them Friday, Saturday, Sunday. Into these sections I arranged the respective props we would need. Bottles of fake blood. Polaroid camera and film. Rubber knives and machetes and their metal siblings. A towel meant to sop up an oozing wound. An empty whiskey bottle and a jug of apple juice. Two versions of the same calendar and a sharpie. Several red folders with several paper-clipped files within them. A dozen different versions of the same photograph (that needed to be crushed in a hand and would no doubt require multiple reshoots). Fishing line (for invisibly dragging shut a door).

The organization of the shoot was similarly laid out—on the surrounding walls. Ben Enke, the DP for 13th Night, had visited town several weeks prior. We spent the day going through every beat of the script with the storyboards in hand. He snapped a photo of each shot, using an app called Cadrage that logged the framing and the type of lens he would use.

David Ullman, who served not only as the editor, but also as some version of both assistant director and script supervisor—then printed up each of these photos. On the walls he taped up labels for Friday, Saturday, and Sunday—and beneath each of these headings arranged a shot list study guide for everyone to consult.

He created a redundancy for this in a binder he carried about, marking its pages up with pens and highlighters and sticky notes as the shoot progressed. Some of the marginalia was meant for us (as he made notes about continuity) and some of it was meant for him (as he would later be the one editing this mess of coverage into a tight fifteen minutes).

Despite all of this—the prop table, the shot list, the binder—we missed something.

I’ll admit that shooting out of order messes with me. I have the script solidly in my head, but the shot list scrambles it. Setting up the lighting and arranging the camera takes an annoying amount of time, so limiting the number of set-ups is essential. If we’re shooting in the garage for a scene in the first act, then we’re staying in the garage for a scene in the second act as well. Sometimes this makes it feel like someone has scissored up the story and tossed its confetti in the air while a fan is blowing. Without David’s organization, I would have been lost many times over.

The fact that we missed only one shot feels miraculous. The front door was supposed to slam shut, as if blown by a wind. I had the fishing line (to tie to the knob) on the prop table, but we didn’t have the moment storyboarded or photographed in the shot list.

By the time I realized this, we had moved on to another room, another set-up, another scene, and we didn’t have the time to go back. After that “Oh, shiiiiit” realization, we quickly huddled up and brainstormed a solution—the same way we had the problem of the broken glass and the bloody feet, only this was in real time.

Keep in mind that this wasn’t just a shot. This was the final shot. The end of the movie. The last impression we would leave on the audience.

As it turned out, the substitute was better than the original idea.

We were going to be shooting outside the house later. What if, we proposed, this was the vantage of the final frame? Station the camera at the end of the front walk, so that Jacob stood in the orange glow of the open doorway. He would be the one to slam shut the door (not an invisible force). The moment would resonate all the more, because we could see him retreating into his prison, retreating into himself, underscoring the possibility that this entire supernatural episode might have been conjured by his damaged mind.

As we settled on this, I could feel my blood pressure and cortisol levels lowering, a crisis averted.

Day for Night

I used the write the scripts the same way that I wrote comics and novels: without any regard for budget.

I have a novella—called The Uncharted—about a tech company that sends a group of young adventurers (who host a YouTube stunt channel) to map out the so-called “Bermuda Triangle of the North,” a section of Alaskan wilderness that keeps swallowing people up…only to discover that some areas are uncharted for a reason. I adapted it into a feature, and my reps submitted it, even as they told me it would be a long shot.

I didn’t understand what they meant until we started to hear back from producers. “This is awesome, but it’s also all outdoors, mostly at night,” and “Get back to us with a horror script we could shoot for three and not thirty million,” and “Is there a version of this that doesn’t have a plane crash, ocean scenes, and wolves?”

Still, the impact of a budget didn’t really sink in until I was on the set of Summering, a feature I co-wrote with director James Ponsoldt. In one scene, the characters walk down a street while talking. Simple enough, yeah? Something I never would have thought twice about writing—until I understood the street had to be cordoned off by cops, until I learned that the businesses on the block all had to be paid for the money they lost over the six hours the cast and crew were stationed on their doorstep.

One of the critical scenes—at the end of Summering—is a séance that takes place on a lightning-lit night. When I pulled up to the house where we were shooting, I saw a small army of dudes in cargo shorts and baseball caps surrounding the residence with scaffolding. Inside of this metal exoskeleton they set up LED lights (to simulate lightning) and rain machines (to lash the windows). This was all skinned by thick black fabric, creating a day-for-night shoot. It might have been a cloudless day, but inside that house, it was a dark and stormy night. Again, a learning experience for me. In two ways…

One: folks like to keep regular hours. If your movie has a scene that takes places outdoors at night, the cast and crew are going to be up until 3 AM and wiped the hell out. If you set that scene in the woods, far from any amenities, then they’re also going to be grouchy about the porta-potties and the possibility of being eaten by a bear.

Two: one of the most difficult things to control is the light. You only have so many hours to shoot a scene and then the sun occupies another corner of the sky and makes the shadows lean in another direction. Or there are clouds. Or there aren’t clouds. Or there are clouds and rain. Or there aren’t clouds and rain.

With these things in mind, I didn’t want my cast and crew on 13th Night to be exhausted and grouchy. This was a short film; they were already making sacrifices to be a part of it. So I was committed to shooting during the day and sending everyone home at night to recover.

I also didn’t want to fuss over sunlight or moonlight or weather of any sort. So not only would the story be set almost entirely inside, but we would pull the curtains, lower the shades, and black-out the windows.

There was a story justification for this: in 13th Night, Jacob has not only fortressed himself in this house; he might also be lost in the prison of his mind. But for practical reasons alone, it just made sense: we wrapped the windows. Just like that séance scene in Summering, this would be a day-for-night shoot.

What I didn’t anticipate was how weird this would make us all feel. If you’ve ever visited a Vegas casino, you know what I mean. Hours pass and you have no real notion of time’s passage. In a way it suited the otherworldly material.

There was a complication to factor in to the final sequence. In it, Jacob once again approaches the foyer, when he hears the door reconstitute itself. He and the agent have settled their business, and it’s time for them to part ways. During this final faceoff—with Jacob on one side of the threshold and the agent on the other—I wanted the space outside the house to appear as a black void, as if the agent had stepped from our world into a dimensional rift.

But… right across the street from the house was the Carleton College chapel. It’s a beautiful, stately building, so they keep it lit up at night. This was hardly the backdrop we wanted.

We discussed several solutions. One was an LED wall, powered by Unreal Engine, located in the Twin Cities. We could shoot in front of that and splice the footage into the frame of the doorway. But that seemed overly complicated and would add another day to the shoot. Another was hanging tarps or drop cloths or some kind of blackout drapery from the gutter over the porch, but the spring and fall are often windy in Minnesota, and I didn’t want to run the risk of a gust rippling or even ripping the fabric.

I contacted a local theater and asked if I could borrow the backboards for their set, but they turned out to be too short. I contacted a local construction company and asked if they had any spare plywood sheets lying around, thinking that I could paint them or wrap them in black fabric, boxing in the porch. They did not have any plywood, but they recommended I stop by Menard’s and pick up some fiberboard sheathing. The pile of boards I located had been rotting and crumbling and collecting dust for years, so it wasn’t an option either.

But I found a solution on another shelf. Pink foam boards. Their 4’ x 8’ dimensions fit perfectly under the porch roof. I spraypainted them black and duct-taped them together—and voila!—instant void.

Or maybe not instant. Because I had wasted hours overthinking a simple solution.

I’m reminded of the moment in Star Trek (2009) when Kirk, Sulu, and a doomed red shirt plummet from space into the Vulcan atmosphere. Abrams initially experimented with harnesses and CGI and then realized an easy solution. Mirrors. The actors would stand on mirrors angled to reflect the sky—and no one knew any better.

Pink foam boards for the win.

When Things Go Wrong

I asked some of my director pals for advice going into the shoot. They all said the same some version of the following: “Something’s going to go wrong. Be ready. Stay cool.” And they were right.

I was thinking of them when I missed that shot of the front door. But things worked out. We pivoted and found another, better way.

I was thinking of them when the first shot of the day kept getting screwed up by a timing delay—and so we were starting our day forty minutes behind. But things worked out. Another shot, which we expected to take an hour, took only ten minutes.

I was thinking of them when the Polaroid camera burned out its flash, and we didn’t have a replacement. But things worked out. The gaffer replicated the effect with his lights.

I was thinking of them when the fog machines filled up the house and set off the fire alarms and we discovered that the windows were painted shut. But things worked out. There might have been enough fog in that house to cause a meteorological disturbance throughout the upper Midwest, but a few strategically placed box fans cleared the air in twenty minutes.

And do you know who kept me calm throughout this process? The gaffer, Tom VandenDolder. He never stopped smiling, not that I ever saw, throughout the entire shoot. A self-proclaimed laser enthusiast, he was endlessly good-spirited and energetic, jogging everywhere. He would scramble up ladders and onto apple crates, manipulating the lights. He would crouch under chairs, out of frame, while toggling switches. And he would say something repeatedly throughout the day while clapping us all on the shoulders and offering up fist bumps. “It’s a good day.”

When he said that, he reminded me of something simple and true. All of the hundreds of hours I had spent trying to get to this very moment were based on one thing: a love for film.

Today was a good day indeed, Tom. Because we got to make a movie.

Part 5—“Rough Cut”—will be on the site tomorrow.