On a Tuesday in December, we put my mother on palliative care, the final step on her long walk with cancer after her 2021 diagnosis. She died the following Thursday morning, ahead of her doctor's predicted timeline. I was lying in bed in my parents' house, where I'd been living since my separation from my ex just a couple months prior, when my father called out to me from downstairs with the news, which was a mercy. Shocks, as Christopher Lee counsels Edward Woodward in Robin Hardy's The Wicker Man, are so much better absorbed with the knees bent, or in my case, splayed out and prone.

Several hours later, I arrived at the hospital to meet my dad and older brother, who both arrived ahead of me, to sit with Mom for the last time. I felt like I'd been ripped off. Knowing she was coming to the end, I had time blocked off on my schedule to visit her that Thursday, to spend a final morning with her, to catch her up on my doings, and show her pictures of my daughters, whom she loved, and loved to spoil.

She never got to knit with pink before the birth of my oldest; she was given two sons and grandsons, and while that never threw off her emotional physics in regards to how she cared for us, there was a piece of her, I'm certain, that longed for a girl. (This, among many other reasons, explains why people tell me to this day that I have “feminine energy.”)

Death is just another state of being if you ask me, and hardly an excuse not to chat. Once the necessary hospital staff, from nurses to grief counselors, had rotated in and out of the room to administer the delivery of supremely unhelpful advice (and, in fairness, some genuine condolences), and once my dad and brother had left, I stayed. I talked. I had so much I wanted to say to her: that I would miss her, that I wasn't sure how to look after Dad anymore.

That I regretted not coming around more often after her hospitalization in November, that I would uphold the promise I made to her the day my firstborn arrived and changed our world, to “punch out a bear” for her if I had to. I told her how angry I was at her for not letting Dad and me help her down the stairs the morning that she fell and fractured her hip, this being the reason she was admitted to the hospital in the first place. It may not be the reason she died, because cancer's one insidious motherfucker, but it sure didn't help.

I told her that if I could be reborn, I'd want to be her child again.

All of my words were met with silence, of course, which I'm sure reads as an unsettling sensation on paper, and isn't much less so in practice. But I very much needed to have that one-sided conversation to satisfy my grief. The idea of Mom's death didn't feel real at first, even though we knew her death was inevitable and likely would precede anyone else's.

By the time I'd said my piece to mom's body, though, it did, at least as much as the loss of a parent ever feels “heal.” (One of the participants in the group therapy I attend opined that we do not know how alone we are in the universe until our parents die. I still have one parent left, but I can already say with confidence that he's correct.)

It's this experience that Julia Max centers in The Surrender, her feature debut, a clean, macabre, and refreshingly creative “grief trauma“ horror film built upon impeccable performances from Colby Minifie and Kate Burton, playing daughter-mother duo Meagan and Barbara. With her father, Robert (Vaughn Armstrong), bedridden and in near-constant agony only blunted by routine morphine injections, Meagan has come home, ready to say her last goodbyes and to help support Barbara.

But Barbara's the stoic sort, and a battle ax on top of that, sharp-edged and quick to slash at Meagan for leaving home in the first place. For all the mind-shattering terror and gruesome visuals Max mines from the deep, dark Hell where she takes her audience in the film's latter half, many of its best moments are those where Minifie and Burton spar on screen.

But the realest moment Max constructs with her leads is in bed, with Robert's body on the morning of his passing. Meagan and Barbara fall asleep next to him the night before and wake up gobsmacked to find that he's shuffled off his mortal coil. (They also find that rigor mortis sets in surprisingly fast.) It's in this scene where Meagan makes the same observation as I did on that morning with my mom: “It doesn't feel real.” She is 100% correct.

Nothing about losing a beloved parent feels “real.” For many of us, our moms and dads are the people we've known the longest in our lives, our strongest existential “constants,“ and who we first loved. When Mom died, my aunt, (her older sister) sent my brother and me a line by the Victorian poet George Eliot, aka Mary Ann Evans, in the spirit of comfort: “Life began with waking up and loving my mother's face.” I hold this to be true.

It's not explicated in The Surrender whether or not Meagan has the same feelings about Robert, but it's safe to say that her feelings toward Barbara are somewhat more rancid. Maybe Evans'words applied to her once, but they hold no meaning in the film. Rather, this is a movie about reconciliation between estranged family, with Meagan and Barbara both throwing body blows at one another up to and just after Robert's death.

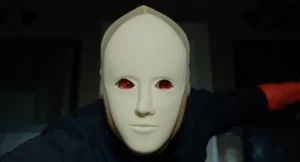

Eventually, Barbara reveals the reason for all of her quirky and bizarre post-mortem dictates, being that she believes it's possible to bring Robert back from beyond the grave and that in order to do so, she and Meagan must destroy all of his physical possessions and any heirlooms or keepsakes tied to his memory, and that she must also pay an exorbitant sum of money to a forbidding, grim-faced shaman (Neil Sandilands), to conduct a ritual of resurrection.

Meagan’s resistance to Barbara’s insistence gives way fast enough. It must, or else there would be no movie. Just as Robert’s death bears a surreality that Meagan struggles initially to process, so too does Barbara’s coping strategy, and while my dad didn’t go to the lengths Barbara does in The Surrender, his own attempts at coping likewise kept Mom “alive” in their own morbid way.

For instance, maintaining their laundry list of “patterns,” as he blandly calls them, which aren’t “patterns” at all and which I suspect weren’t “theirs,” but just “his,” because domineering obsessive-compulsive behaviors are several state lines away from constituting “patterns.” Or writing a Valentine’s Day card for her and placing it at her spot at the dining room table, where he insisted I sit after her death, as if he saw this as a distinct honor when in fact, I found it fucking mortifying.

The ritual in The Surrender goes disastrously, as if anyone would expect otherwise. It’s a horror movie. Human curiosity and, for Barbara’s part, hubris tend to be rewarded with mocking reprisal in our beloved genre. In this case, a cold and dim underworld inhabited by cannibalistic dead and worse creatures than that, colossi towering in distant shadows. I’ll pass on a trip to the awful liminal space where Meagan and Barbara end up trapped during the film’s second act through its finale, thanks. (In a minor stroke of irony, it’s my one major critique of Max’s plotting that we spend so little time in that space compared to the mansion where most of the story is set.)

At the same time, I understand her reckless plan better than my dad’s demand that everything should stay the same now that Mom is gone. Barbara accepts Robert’s death and tries to do something about it (which means her acceptance is strictly literal). Dad can’t bear to accept that Mom is dead, and his denial manifests through his own mundane rituals.

As Barbara’s inexorable will is done and things go from bad to worse in the film, Meagan became my guiding star. In no small part because Minifie, more than most actors in contemporary horror, has a face made to convey the terrible realization of how small humans are on a cosmic scale. Even as Meagan wrestles aloud with the incomprehensibility of her dad’s death, she never acknowledges his mortality as anything less than “real.” Because, in the end, and as I myself learned that morning with Mom, death never feels real; it simply is.