Drafting Evil

Monster is my favorite word. Not just for the meaty phonetics—the sound of someone opening their mouth eagerly, delivering a groan or a half-heard “C’mon”—and then hurrying that tongue forward for a taste, the saliva pop of “-ster,” like the beginning of a chew. It’s also my favorite word because of the joy and terror built into the definition.

As a comics writer, I’m constantly dreaming up monsters—and then working with artists on their designs. Sometimes this involves a slight modification to an existing model. For instance, I wrote a Xenomorph story—called Aliens: Aftermath—that was supposed to be a follow-up to James Cameron’s film. I was essentially shouldering a narrative between Aliens and Alien 3. I set it on bomb-ravaged LV-426, as a series of rogue journalists (including the nephew of Private Vasquez) investigate what happened here. A nuclear winter has set in, and the surviving Xenomorph—who hunts them down—has been soaked in and altered by the radiation. An atomic alien, I called him. Translucent and glow-in-the-dark.

I could fire off dozens of other examples like this, including Omega Wolverine (who comes from the future and is infected with a phalanx virus) and Hellverine (who has a flaming skull and flaming claws).

Jim Lee once told me the best character designs can be recognized in silhouette and that’s certainly true for many of our favorite horror baddies. You don’t need a flashlight to know Freddy or Frankenstein’s creature or Pinhead is emerging from the shadows. I kept this in mind when Cory Smith (the artist) and I created Exhaust, a villain in Ghost Rider who looks like someone rode a Harley into a wood chipper, a coughed-up combo of exposed muscle and bone and chrome piping.

Designing monsters from the ground up takes time and (usually) many failed iterations before you nail the look. That was certainly the case with 13th Night.

In Part 1 of this series, I talked about how my first stab at a script didn’t account carefully enough for the budget. The shoot required multiple locations, too many characters, stunt work, elaborate special effects, emergency vehicles, an accident at an intersection. It was all too much for a meager microbudget—including my monster.

I wanted a reaper. An agent of Death. (The Agent.) I had sketches drawn up of bony and spectral figures. Matt Bowers (who was simultaneously drawing up storyboards) tried a take on a traditional hooded creature that looked like it had been buried for a thousand years, the fabric of its cloak clotted with mud and sticks and dead worms. I shared this concept with a VFX artist who quoted me 10,000 dollars for the build and a single moving puppet hand (with long, rotting fingers).

This was not possible. So what was?

I stood by my shelf of DVDs, pawing through the titles, dredging up fearful memories. I needed something simple and manageable—but iconic. All Michael Myers required was an expressionless white mask and gas station coveralls. How could I do more with less?

Several images began to coalesce in my brain. The Tall Man in Phantasm. The so-called Mystery Man in Lost Highway. And Reverend Kane in Poltergeist II. They were close cousins in their design and chilling in appearance—a look that didn’t require more than a black suit and a ghoulish pallor. My villain was an agent of Death, so it made sense that his costume be similarly… funereal.

Nat Wilson is a pal of mine (who also happens to be one of the funniest people I’ve ever met). He’s not a trained actor, but if you’re around him more than five minutes, you’ll witness him perform. He’ll pretend himself into a T-Rex and chase his children through a park. He’ll assume a Texas accent and improvise a pork-and-beans monologue. There’s no one he can’t mimic. I enlisted him in a zero-budget production, and he proved himself both a natural performer and a good sport (allowing me, at one point, to soak his entire body in fake blood). I thought he would be a perfect fit for 13thNight for a few reasons.

Actors often have one or two exaggerated features that make them more interesting to look at. Anya Taylor-Joy of The VVitch, for instance, has eyes that are bigger and farther apart than most, giving her a dreamy, feline appearance. Robert Englund has a sunken mouth and a prominent nose and chin that kind of curve toward each other like the pincers of a closing claw, making him appear like a smirking predator even without the Freddy Krueger makeup. Nat has the chin and cheekbones of a senator, but this strong, sculptural appearance is bored through by black eyes. Shark Eyes, his friends used to call him in college. His pupils can’t be distinguished from his irises. His gaze is naturally unsettling. He also has large hands that bend backwards at the knuckles and appear like bald pale spiders. I knew, with the right make-up, he could scare the hell out of an audience.

But there’s much more to a monster than its look. Writing for comics has taught me the importance of the visual signature. I’m talking about the costumes, yes, but more than that, some posture or behavior that is the character’s calling card. If you think about Superman, you think about Clark Kent stepping into a phone booth, ripping open a buttoned shirt to reveal the shield on his chest. If you think of Batman, you think of him crashing through a window while tossing smoke bombs. If you think of Wolverine, you think of him popping his claws with one hand and crooking the finger of the other, beckoning someone into a fight they won’t win.

I spoke with Nat about embodying the physicality of the character. We decided a stiff efficiency would inform his movements. He would not move unless he had to, and when he had to, his movements would be as minimal as possible. When he shoved Jacob, his body would remain rooted in place. Only his arm would unfold, a flat-handed strike that exerted no extra energy. When he picked up a Polaroid off a kitchen table, he would pinch its two corners and raise it like a forklift. Only when the photo had traveled a foot through the air would he pause its ascent, and then lower his eyes to note its placement, and then lower his head to catch up with his gaze. You could almost hear the bony gears and levers operating inside his flesh suit.

He would never blink, his gaze constant and hungry. This would prove to be especially troublesome when we fired up the fog machine, but Nat was committed to using his eyes as a weapon.

And then there was the smile. With the exception of one critical shot, the Agent’s face is arranged in a rictus of sick pleasure, his grin so severe that Nat’s face would shiver slightly from the effort. Nat wanted to sicken the audience by making clear how much pleasure he took in the suffering of others.

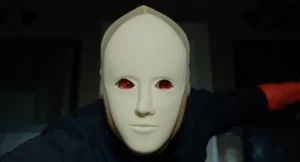

For one stupid day, I debated whether I could cheat on the cosmetics and buy a kit and figure things out on my own. And then I quickly wised up and hired an artist named Amy Dills, who drove down to Northfield for a makeup test. Over two hours, we treated Nat like a canvas. She painted necrotic colors onto Nat’s skin, smeared gray tones across his lips, shaded blackness into his sunken eyes and cheeks. His hair was plastered down, helping emphasize a skull-like visage.

But I hoped for one more thing to drive home the eeriness. No eyebrows. We couldn’t make them with makeup along, and Nat (understandably) didn’t want to shave them. Silicon covers seemed like the only option—what were essentially bald caps for his eyebrows. The trouble was, they had to be ordered, arriving just in time for the shoot.

So Amy didn’t have a chance to practice until the first day of production. There are only so many different ways to express the same message: “How are we doing?” “How’s it going?” “How much longer?” Even as we shot other scenes, I continued to pop my head into the bedroom and check on Amy’s progress. Thankfully the morning’s scenes took longer to shoot than expected, because Nat didn’t emerge from makeup for two and half hours.

Thankfully he looked hideous. Gloriously hideous. His brows—shelled beneath the prosthetics—made his expression feel not just uncanny but obscene.

I had my monster.

Mirror, mirror

Monsters. Villains. Antagonists. However you want to refer to them, they’re the sexiest, most fascinating part of your story. In fact, they’re the reason the story exists at all. Because only trouble is interesting. And they’re the trouble.

But more than that, they’re an external manifestation of what your hero is struggling with internally. Here’s the comics version of what I’m talking about. If Batman is fighting Mr. Freeze, the story should be about Bruce wrestling with his emotional coldness. If Batman is fighting Killer Croc, the story should be about Bruce taming the savagery within him. If Batman is fighting Two Face, the story should be about whether Batman is the mask and Bruce Wayne is the man, or Batman is the man and Bruce Wayne is the mask.

Let’s consider the horror story equivalents. In Stephen King’s Misery, Paul Sheldon battles Annie Wilkes; in doing so he overcomes the controlling grip of toxic fandom and his own self-destructive behaviors. In Jordan Peele’s Get Out, Chris Washington fights the Armitage family; in doing so, he faces off with the dangerous complacency of white neo-liberals and escapes the racial systems that trap and prey on him. In Neil Marshall’s The Descent, Sarah battles albino humanoid cannibals while lost deep in a cave system; in doing so, she finds a way to surmount the hollowed-out loss that follows the death of her husband and child in a car accident.

The external struggle only means something because of the internal struggle. So the monster becomes a manifestation of the lead character’s poisoned heart and soul.

In 13th Night, Jacob is a weary, troubled war vet who proved himself so good at killing that Death wants him to continue to deliver. His daughter is held hostage, by her illness, as blackmail. If Jacob doesn’t follow through on his kill list, then Caitlin will be claimed.

You already know about the Agent’s black suit, but I knew I needed to take things further. Crank up the dial. Make the figure instantly recognizable in a lineup. This is where the American flag tie came in.

If the hero and villain are inexorably twined, and if my hero was an exhausted veteran who may or may not be imagining this nightmare of a trap he finds himself in, then it made sense that the villain would epitomize the American war machine. The black, slim-cut suit—and the stars-and-stripes necktie—made the Agent look like a gargoyle of industry. Someone who coldly gobbled up others for the sake of profit and power.

Their opposition extends to every ingredient cooked into the characters. Jacob has long wild hair and a beard, whereas the Agent appears hairless except for a slick black smear of hair that might have been painted on his skull. Jacob moves almost animalistically, pacing rooms, curling around corners, cutting the air with fists and steel, whereas the Agent practices an eerie stillness. Jacob wears practical gear that is weather-beaten and battle-worn, whereas the Agent is neatly and stiffly packaged in a suit. Jacob grimaces, the Agent grins.

I wanted to find ways for this oppositional theme to play out in the staging and design of the production. So reflections can be seen throughout the short. Jacob takes a Polaroid of each of his victims. Jacob flicks his haunted eyes toward his rearview mirror after he drives home from a killing. We staged the bathroom shot from above, so that the mirror reveals two versions of Jacob washing the blood off his hands. We hung long mirrors on either side of the dining room table so that when Jacob and the Agent sat opposite each other, they would be twinned in more way than one. We stood them on either side of a doorway, one in light, the other in shadow, their postures mimicking each other.

Voicing the Darkness

Maybe it’s been years since you saw The Silence of the Lambs, but even now, you can still hear the clipped consonants and elegant diction of Hannibal Lecter, his voice sounding like someone cutting meat on fine china. You cringe at the memory of the Babadook emitting his strained, guttural cry. Jigsaw’s pragmatic delivery is as chilling as his traps. The teasing nastiness of Ghostface uttering, “Hello, Sidney,” is etched into our ears with a knife. Regan’s rusty, croaking, cigarette-ravaged voice in The Exorcist might beat out the pea-soup vomit as the most nauseating thing to escape her mouth.

The sound of the monster matters.

When the credits rolled, I wanted the viewer to question the reality of 13th Night. They should wonder whether they were actually witnessing a supernatural force at work? Or trapped inside the prison of Jacob’s broken brain? I knew that the voice of the Agent could not only horrify the audience, but also highlight this uncertainty.

Nat had been practicing and recording several possibilities. We settled on a way of speaking that sounded scarily confident, but old and ravaged, as if wind and dust were blowing through holes rotted in his throat.

But here’s what I told Nat: I don’t actually want you to speak on set. We would record his voice work later and layer it into the film.

There was a practical reason for this. The voice was a strain for him, and he had to contort his face and tense his neck to produce it. This didn’t match well with the characterization, as we wanted the Agent to appear in complete control at all times.

There was also a thematic importance to this decision. If the Agent’s mouth never moved, when we heard the voice, it would feel disembodied, possibly imagined from the cell of Jacob’s head.

And—here’s the fun part—we could make the Agent sound even scarier with the help of our sound mixer. Kent Militzer is someone who worked for Hollywood for decades before moving back to his home state of Minnesota during the pandemic, where he founded a company called Uproar Sound. He is a kind, funny, wooly musician and sound engineer, and he generously offered to help us out for a ridiculously low rate, because he believed in the script and wanted to have some fun doing something different than the commercials that so often busy his schedule. When I shared Nat’s dialogue recordings—and when I asked for ways to amplify its eeriness—he gave me a whole menu of options.

Give this a listen…if you dare.

You can hear a whistle of wind, but there’s something else…something you can’t quite put your finger on…a vague undercurrent of noise. That’s a soft version of the dialogue read backwards. This is my kind of Black Sabbath audio sorcery.

My monster had come hissing to life. But my greatest adversary still awaited me. The three-day production. With a blend of dread and excitement, I was crossing days off the calendar—and prep tasks off my checklist—as the start date approached. What was imaginary was about to become real.

Part 4 of this series—“In the Dark”—will appear tomorrow on the site.